Tactical Preview III: EURO 2022 Quarter-Final Series; Sweden vs. Belgium

Things should be straightforward for Sweden, but this is knockout football and they might be missing some key personnel.

I currently keep all of my women’s football content free. Consider subscribing so I can continue to do so and to gain access to the full archive, where you can read paywalled articles on the men’s Champions League final, N’Golo Kanté’s underrated offense, and the evolution of defensive compactness.

I am running a forever-lasting discount for the duration of the EUROs (ends August 1st):

This is the third article in a tactical preview series on the EURO 2022 quarter-finals. They will be published chronologically on the morning of each game.

You can return here to find each piece, which will be hyperlinked below when they are published:

England vs. Spain [July 20]

Germany vs. Austria [July 21]

France vs. the Netherlands [July 23]

Sweden

Formation/s used: 3-4-3; 4-2-3-1

Results: 1-1 D vs. Netherlands; 2-1 W vs. Switzerland; 5-0 W vs. Portugal

Analysis

Peter Gerhardsson is both a good coach and a Grade A troll. After ditching a 4-2-3-1 in favor of frequent 3-4-3 experimentations in the lead-up to the 2021 Olympics, he proceeded to utilize only the former shape in tournament play. The decision seemed to indicate a decisive switch in Gerhardsson’s preferences and the return of the 4-2-3-1’s preeminence.

So, of course, Gerhardsson went with the 3-4-3 in his side’s EURO 2022 opener vs. the Netherlands.

That peculiar unpredictability aside, Sweden have one of the clearest, most consistent tactical identities of any international team in the world. Their excellence begins against the ball, where they institute a high press famed for it’s club-like levels of organization and intensity.

The assignments and structure from the 3-4-3 tend to be variable. Against the Netherlands, LW/LF Fridolina Rolö frequently pinched inwards to check a central midfielder when the ball was on the opposite side. Meanwhile, Kosovare Asllani would press the left center-back as Sweden’s RB stepped up to maintain access to the Dutch LB, creating an asymmetric 4-4-2 look.

In the event of circulation to the other wing, Rolfö would spring out to cover the flank while Asllani dropped to mark the far-side midfielder (a member of Sweden’s double pivot would take the CM Rolfö abandoned).

If that sounds kind of confusing, it’s because it is. Most teams would get shredded if they had to operate in such a see-sawing system, but Sweden aren’t most teams. The chemistry between their veteran core is impeccable and each player seems to possess a master’s degree on the nuances of pressing as an individual — body shape, angled runs, awareness of teammate positioning, understanding of contextual compactness within the logic of the larger scheme, aggression, work-rate, etc. — offering Sweden a remarkable level of in-game flexibility on defense.

This is not to say that this particular press is invulnerable; in fact, the Netherlands found some joy in the second half when they sought to exploit Glas’ back-and-forth coverage down the right flank, repeatedly putting Sweden’s center-backs in uncomfortable situations.

However, that is only one option for Sweden to turn to. The 4-4-1-1 structure from the older 4-2-3-1 tends to be a lot more rigid and a tad harder to break down. In it, the front two negates the typical 3v2 overload in textbook fashion, enabling Sweden to force possession to the touchline. From there, the Blue and Yellow compress the space and press with ferocity.

Sweden’s emphasis on winning the ball high makes them one of the most dangerous offensive transition teams in the world. As Arden Holden writes in this article, Sweden are constantly primed in rest attack, meaning that players are always preparing themselves for potential breakaways in certain defensive situations.

The Olympic finalists are also great when transitioning from deep, using Asllani’s movement and aptitude for the through ball to release runners in behind.

Sweden’s primary limitations exist vs. deep blocks. They lack that progressive oomph deeper in midfield, with mainstays Caroline Seger and Filippa Angeldahl selected for their steel more than anything else. As a result, Sweden can be over-reliant on Asllani to find central penetration and have to turn to fast combinations down the wings to destabilize defenses.

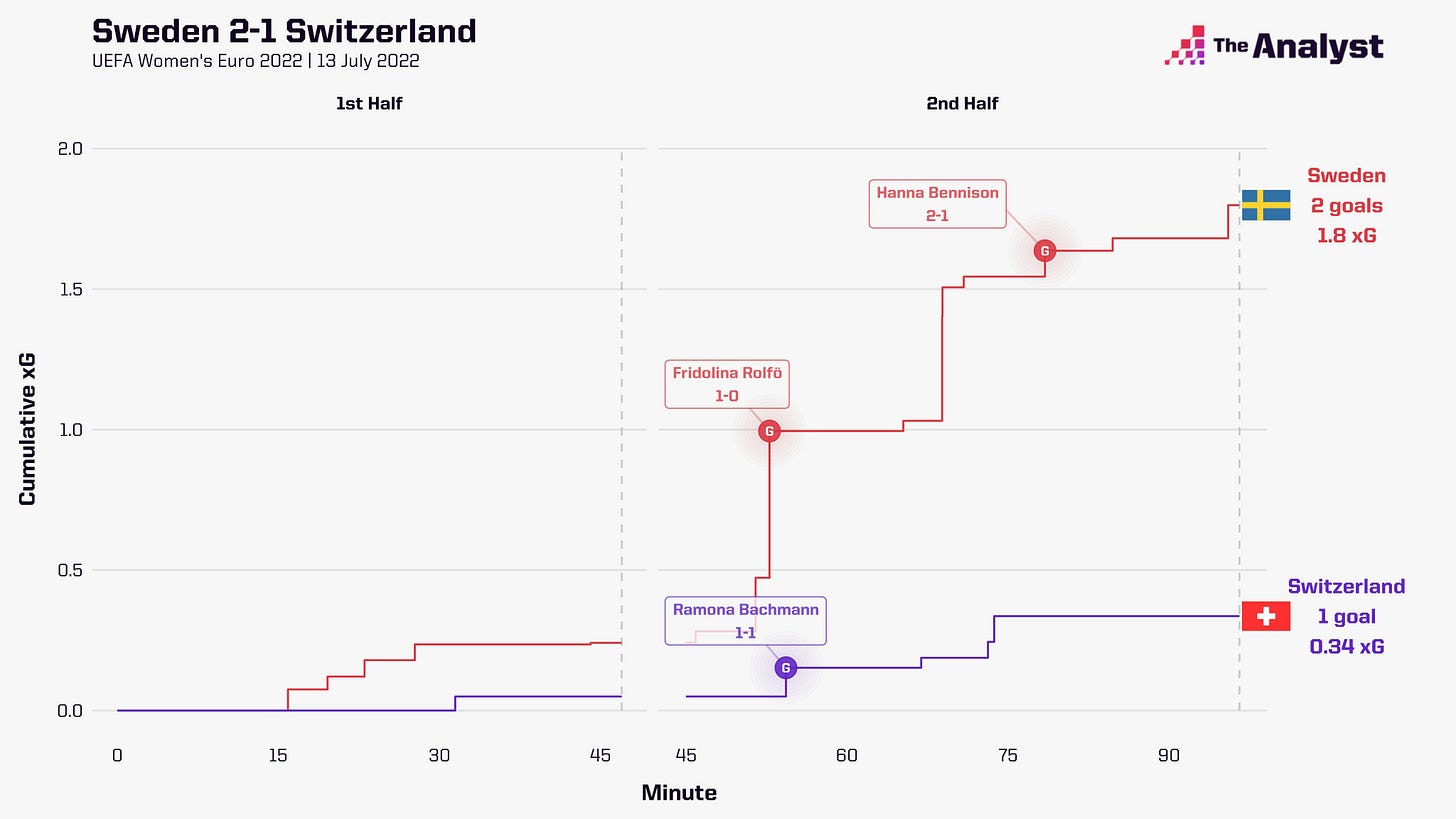

If rivals give them space, those two solutions can be enough, as was evident vs. Portugal. But Sweden struggled to create much of anything for forty-five minutes vs. a disciplined Swiss outfit and lost control of the second half vs. the Netherlands, costing them points.

On the flip side, Sweden fully maximize their set-piece potential, often crowding and obstructing keepers to give their Nordic height a platform to shine. This provides Gerhardsson’s team with an out when things have become stagnant vs. a stubborn block.

Belgium

Formation/s used: 4-2-3-1

Results: 1-1 D vs. Iceland; 2-1 L vs. France; 1-0 W vs. Italy

Analysis

Given that Belgium created less chances and xG than their opponents in all three group stage games, it’s easy to assume that they shithoused their way to the knockout stages. On the contrary, the Red Flames sought to take the initiative when they could, playing the ball around with zip and in concerted patterns.

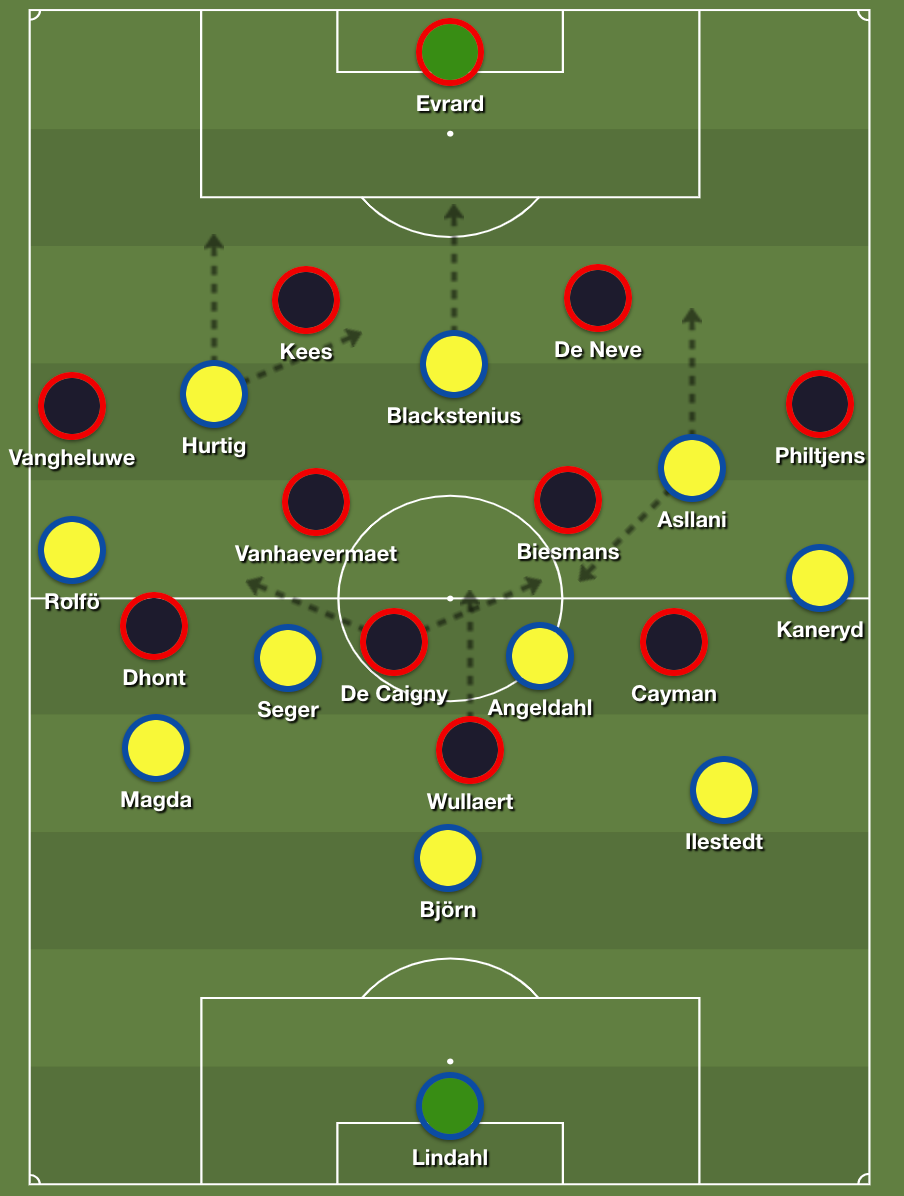

Belgium’s most common mode of progression occurs down the flanks, where the fullbacks seek to find wingers Janice Cayman and Elena Dhont on the touchline or in the halfspaces. These deliveries act as triggers for a quickened tempo, as Belgium try to leverage the initial ball into combinations or as a precursor to getting inside the block.

The dynamics between the wide individuals and the central duo — Tessa Wullaert and Tine De Caigny — are crucial to making this relatively straightforward scheme function. Wullaert and De Caigny are keen to offer support to Cayman and Dhont, whether that be presenting as a short connection or making a run in behind. At times, some of the front four will even interchange, adding a degree of spice to their attacking patterns. This creates a base for one of the members of the double pivot to burst forward opportunistically, exploiting any room Wullaert or De Caigny vacate, thereby providing more offensive potential and variety through what are essentially third-player actions.

As a secondary option, Wullaert will drop off the front line to receive to feet and help Belgium break lines lines vertically. De Caigny is comfortable rotating into the forward line, while the double pivot are ready to receive from Wullaert and spray the ball ahead.

Although Belgium clearly enjoy playing on the ground, their overall offensive approach is mixed. They will test the integrity of back lines with a number of long balls from a variety of different locations (sometimes, it’ll be from the back; other times, it’ll be from higher up, with a winger dipping inside to ping balls over the top; and, on a few occasions, it’ll manifest as clipped balls into the front line from midfield).

Defensively, Belgium are similarly straightforward, configuring themselves in a 4-4-1-1 similar to Sweden in concept; one of the front two denies the pass into the DM in an effort to force play wide. However, the level of execution and intensity is understandably different, with Belgium preferring to contest opponents from a mid-block stance. Their ball-oriented stance — meshed with a lack of pressure on the ball — can leave them susceptible to switches, as was the case vs. France.

Ultimately, Belgium are far from an elite defensive unit and have relied on the heroics of goalkeeper Nicky Evrard to take them to the quarter-finals.

How They Match Up

This match will likely be a typical case of David vs. Goliath. Sweden will have most of the ball and will push Belgium deep into their own half. The latter’s best hope is to stay as compact as possible, pray that Evrard can continue to work miracles, and find something crafty on the counter through the synergy of their front four.

Belgium are reasonably skilled in possession but simply do not have the caliber to truly test Sweden’s press. I could suggest fancy adjustments, but few but the best sides in the world could execute them. Using Wullaert and De Caigny to set up contests for second balls might be worth looking into, as Belgium’s wingers play narrow and the double pivot does well to fill space further forward (in other words, there is a natural structure for second balls).

From Sweden’s POV, this is about ensuring that things go to plan as much as possible. Already, that is somewhat difficult given the questionable statuses of Hanna Glas and Jonna Anderson.

If they are unavailable, that seriously stunts Sweden’s offense, as their fullbacks are central to their offensive production out wide.

Will Sweden go with a back three to manage? Stick with a back four? Gerhardsson won’t tell (I told you he was a troll) and it’s hard to predict.

But what should be expected are Sweden’s typical defensive intensity and savvy in offensive transition. The main question is whether Gerhardsson’s eleven can prove that they possess another level in possession in unideal circumstances, which would go a long way to putting them squarely back in the conversation as the favorite to win it all.

Additional Reading: