The Evolution of Defensive Compactness

Why attacking is harder than ever.

The luxury player…has faded away with this accent on high-intensity pressing. I mean, you know, it’s not a new thing, pressing, is it? We did it at Arsenal. We practiced it in training till we were blue in the face. We did it very well, pressing from the front.

That’s former Arsenal striker and FIFA video game commentator Alan Smith in a 2019 interview with my Managing Madrid buddy Kiyan Sobhani. He’s responding to a question on how the #10 position has changed since he last played and, in doing so, briefly touches on the relevance of pressing over the course of multiple decades.

If you want some of my thoughts on the larger #10 discussion, I wrote about it here, but that audio bite has always intrigued me: how much has tactics and, specifically, defensive tactics evolved over the years?

Taken in isolation (and for the convenience of narrative), these few lines could be seen as a statement against the idea that there have been noteworthy alterations since Smith’s era. Indeed, analysts and fans probably overestimate the shift in broad, strategic trends. The notion of a game where every player has to possess widely ranging skillsets, rotate into multiple positions, and press to dominate the ball roughly describes the philosophies of Pep Guardiola and Marcelo Bielsa, just as it does of “Total Football” and its emergence 60-70 years ago.

This is not to say that the sport ended with Rinus Michels and Cruyff, but that the adjustments since then are probably to be observed at the granular level. Fundamental ideas like pressing, possession football, attacking fullbacks, etc. have been around forever — it’s in their application (i.e. the coordination between players, intensity, individual and collective mindsets, interdependence between different concepts, and reaction to opposition implementation) and the spread of said application where we see more regular intervals of change.

In other words, pressing might not be new, but its nuances and the way it has been executed have undergone significant improvements while being adopted — in its modern form — by an increasing number of sides.

Pressing is where this is probably the easiest to see; one need only look at pressures data and a video of that old, great Netherland’s team hunting for the ball.

The most obvious difference between then and now is in the “compactness” of the defensive shape.

The Netherland’s extreme ball-focused approach melded lines together into a single, heaving mass that completely clogged the immediate space next to the ball but left plenty of real estate 10-15 yards to the side or in behind.

Today, this would be ripped apart, which is why most current pressing structures seek to adopt a more judicious balancing act in their vertical and horizontal spacing and orientation towards the ball.

While there is much that can be said about pressing and its evolution, I would like to focus on the broader idea of defensive compactness, as that represents the granular change within the the concept that has held true over a lifetime (pressing).

We all have an intuitive idea of “compactness,” but, more specifically, it involves the negotiation between access to the ball, control of space, and control of opponent passing direction — all things achieved by defending as a collective.

Arrigo Sacchi was an early pioneer of compactness in the late 80’s, implementing a zonal system at AC Milan that stood in stark contrast to the man-marking orthodoxy of the dominant Catenaccio.

I used to tell my players that, if we played with twenty-five meters from the last defender to the center forward, given our ability, nobody could beat us. And thus, the team had to move as a unit up and down the pitch, and also from left to right (p. 361).

In the defensive phase, all of our players always had four reference points: the ball, the space, the opponents, and the teammates. Every player had to decide which of the four reference points should determine his movement (p. 366).

Every movement had to be synergistic and had to fit into the collective goal. Everybody moved in unison. If a fullback went up, the entire eleven adjusted (p. 366).

We would line up in our formation, I would tell players where the imaginary ball was, and the players had to move accordingly, passing the imaginary ball and moving like clockwork around the pitch, based upon the players’ reactions (p. 367).

[Emphasis added mine]

- Arrigo Sacchi; taken from Jonathan Wilson’s Inverting the Pyramid.

Instead of relying on a duel-based system at the back and a sweeper to protect the space in behind, Sacchi used structures and regimented lines of defense in close proximity and coordination with each other to control and deny space.

It was a set of ideas ahead of its time (well, except for the insane offside trap) and signaled a new way to press, as well as defend in deeper settings, that was gradually adopted by many of the great sides of the following decades.

And it is with those great sides, such as Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona, José Mourinho’s Chelsea, Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool, etc., where the story of compactness stops in the popular imagination: “Sacchi popularized defensive compactness as it’s understood in the modern sense and it was refined by other excellent coaches down the line” — some twitter analyst, probably.

In terms of the tactical history of great teams, that is accurate enough. Nevertheless, I think that kind of narrative misses out on the proliferation of defensive compactness to a greater number of teams, which has raised the collective tactical level of football as a whole, thereby presenting “big clubs” with the sort of challenges that only they used to be able to pose.

This proliferation has been extremely gradual — driven by cultural shifts and natural coaching turnover that has had to respond to the financial hyperpower (translation: attacking hyperpower) of Europe’s giants — and, thus, can be hard to perceive in the moment, just as it is hard to notice your own inch-by-inch growth as a child.

So, to better get an idea of this evolution, let’s do a side-by-side film comparison of the defensive compactness of two La Liga teams vs. Real Madrid across an eight-year span: Rayo Vallecano in 2011/12 (pre-Paco Jémez) and Alavés in 2019/20. Both sides finished near the bottom of the table — Rayo in 15th, with 43 points, and Alavés in 16th, with 39 points — and neither were good defensively — Rayo conceded 73 goals (worst in the league) and Alavés conceded 59 goals (third worst).

Although the two of them defended in 4-4-2 blocks, you can spot significant differences straight off the bat. Rayo’s spacing is far looser vertically and horizontally and players aren’t moving on a string. There is a general idea of wanting to defend compactly and in lines, but not everyone is fully in tune with their teammates’ movement and positioning in relation to various offensive threats.

This is most visible when the midfielders in the double pivot allow a large gap to appear between them, enabling Ángel Di María to dribble through and attack a significant portion of space.

Alavés immediately appear far more regimented by contrast. There is checking over shoulders, adequate support near the ball, and scant room between the lines. As Madrid switch the point of the attack, Alavés rotate as a team and maintain their shape.

Again, everything about Rayo is looser and farther apart as they try to reorganize from defensive transition, but they do get the ball-side member of the double pivot to support play on this occasion. However, the front two are fairly disengaged from the whole scenario and do little to help out. As a consequence, Real Madrid are able to break through by situating a second needle player on the opposite side.

Alavés couldn’t look more different, quickly floating into an approximation of their preferred defensive shape even though they also have to recover against a Real Madrid counter-attack. This slows the pace of the game and forces the All Whites to attack a set defense. As Zidane’s men play from side-to-side, the front two are heavily involved defensively, plugging passing lanes and delaying Madrid’s ball carriers so that the midfield line can get back into position.

Like the clip says, there’s not much to analyze on Rayo’s defensive sequence.

Alternatively, Alavés’ commitment to sitting deep and choking off gaps between the lines couldn’t be more stark to Rayo’s approach. Madrid are barely able to receive in pockets and keep being forced back and to the side. Eventually, they have to choose to play down the wing, where Alavés have plenty of numbers.

What Alavés did vs. Real Madrid on that day is nothing special by today’s standards and, while they didn’t get smacked 6-2 like Rayo did, Babazorros El Glorioso still lost 2-0. Alavés’ midfield coordination wasn’t perfect and you could say that Los Blancos’ offensive approach had flaws, too, but Alavés’ still looked significantly better against the ball than Rayo.

None of the dissimilarities are major like the Netherlands’ pressing vs. Bayern’s; it’s all about a few yards here and there, communication, spatial awareness, and greater commitment and focus from everyone, especially the forwards.

As a result, one version of Real Madrid found it much easier to cut their opponents apart than the other. The 2011/12 side did good things on the ball, but they only had to do so many of them and for a shorter period of time before they found their way towards goal. 2019/20 Madrid could swing the ball back and forth a dozen times and stick two players between the lines and still not fashion a good box entry against a bottom feeder like Alavés.

Now, this is only one case-study and a small one at that. A singular example does not prove my sweeping thesis. Yet, analyses of broader trends in La Liga have observed the adoption of especially compact blocks in recent years, and what little data we have on compactness (the scarcity of tracking data — not to mention historically — makes getting a large volume of info on a number of competitions difficult) supports the argument that teams are getting harder to break down.

FIFA’s technical report on the 2018 World Cup found that teams were more compact defensively than in 2014, “with a tournament average of 26 meters between a side’s deepest defender and highest attacker out of possession. The amount of space available has been dramatically reduced, making it challenging to find openings” [here’s how FIFA measured compactness].

Carlos Alberto Parreira, former coach of Brazil’s 1994 World Cup-winning team, was quoted as saying:

Space between the lines was practically non-existent at this World Cup.

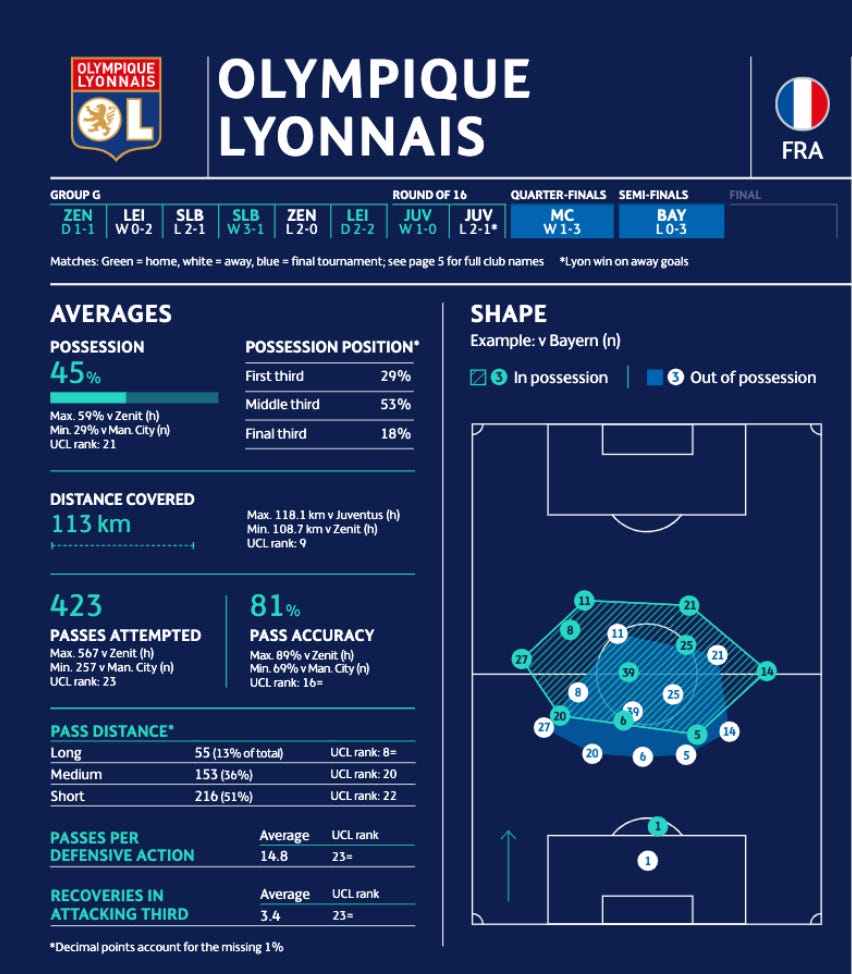

Though UEFA’s technical report on the 2020 Champions League declined to analyze average changes in compactness (probably because a year-to-year change would be much smaller), they dedicated a page to each team and depicted their average shapes in and out of possession vs. a particular opponent, giving you an idea of the defensive shape of a number of modern sides.

Despite lacking specific, all-encompassing data, the numbers we do have, alongside specific and broad tactical analysis and anecdotal evidence, indicates that an increased number of teams are defending more compactly than before.

Perhaps this is why coaches like José Mourinho have appeared to “decline” since the early 2010’s. These days, it simply isn’t enough to place attackers between blocks like The Special One did with Özil, Di María, and Ronaldo — teams are prepared to deny those options. Offenses also need to possess more sophisticated passing patterns, decoy movements, positional rotations, and tempo changes to manipulate defenders, pull people out of position, and exploit holes before they disappear. And all of that needs to be done with a collective synergy and sense of structure that matches or exceeds what’s displayed by defenses.

Positional play (JDP) is one method that tries to do this and has been adopted by virtually every single one of the best attacking coaches, not to mention that elements of it have been widely adopted in teams that haven’t fully given into JDP.

However, I do not want to present positional play as a simple reaction to the defenses we see now. In fact, it was probably the reverse. With Guardiola’s popularization of JDP principles and wild success at Barcelona, low-budget teams looked to improve tactically in order to get better without spending money they didn’t have. This, in turn, likely forced more rich teams to hire JDP coaches (i.e. Bayern Munich, Manchester City, Chelsea, PSG) or ones that incorporated some of those ideas to break down increasingly stubborn defenses and maximize the riches at their disposal.

And, so, tactical evolution goes on like a game of ping-pong; an offensive improvement garners a defensive one and vice-versa. Slowly, the game inches forward, leading to marginal improvement after granular improvement, until… voila! A major philosophical rupture occurs and is termed as the moment of change, forgetting that football is changing all the time — bit by bit. You just have to pay attention (and analyze some film) to notice.

Key references:

Inverting the Pyramid (Jonathan Wilson)

Tactical Theory: Compactness (spielverlagerung)

Journal article: “Collective movement analysis reveals coordination tactics of team players in football matches” (can bypass paywall using Sci-Hub)

La Liga And The Revolt Of The 4-4-2 Formation (José Pérez from betweentheposts.net)

Film found at footballia.net