What Spain Need to Fix Tactically to Win EURO 2022

The secret lies in refining their possession game - both for offensive and defensive purposes.

I currently keep all of my women’s football content free. Consider subscribing so I can continue to do this and to gain access to the full archive, where you can read paywalled articles on the men’s Champions League final, N’Golo Kanté’s underrated offense, and the evolution of defensive compactness.

There is probably no group more pessimistic about Spain’s chances in EURO 2022 than the Spanish themselves. The media’s claims that La Furia Roja should be considered a favorite has been received with much chuckling and eye-rolling; after all, the fans spend the vast majority of their time fretting over all the ways their team could lose.

It’s gotten to the point where it appears as if some of this nervous energy has bled into the squad at times, with Spain’s players and coach Jorge Vilda making a point of emphasizing their lack of tournament pedigree and waving away the favorites’ label in the Arnold Clark Cup.

On the surface, this inferiority complex seems baffling and maddening. Fans of such a collection of talent usually need their expectations brought down to earth — not the other way around.

Yet, this collective psyche is understandable within the historical context of the national team. You only need to go back to 2015 to find a side that had their confidence and competence systematically crushed by an abusive coach in Ignacio Quereda. A coup by the veterans eventually pushed him out, and Spain replaced the old head with current boss Jorge Vilda.

The days of blatant homophobia and relentless verbal assaults seem to be over, but Vilda’s immediate banishment of those who spoke out against Quereda, in addition to his refusal to appear on the documentary that detailed the stories of abuse, have contributed to a sense of uneasiness that constantly looms over any discussion of La Selección. This is without mentioning his bizarre indifference to certain players, such as Damaris Egurrola (who ended up declaring for the Netherlands after Vilda repeatedly refused to call her up) and Maitane.

Thus, every Vilda decision is hyper-scrutinized and every motive of his second-guessed; Spain fans have had little reason to trust their federation for decades and aren’t about to start doing so now. And, you know what? Fair enough.

But maybe it’s time to start trusting the players.

Spain’s Ridiculous Potential

As much as it is true that this team is not Barcelona, it is still the Catalan club’s core that powers performances on the international stage (even absent Alexia Putellas and ex-Culé Jenni Hermoso). Mapi Léon, Irene Paredes, Patri Guijarro, Aitana Bonmatí, and Mariona Caldentey form the spine of an outfit that is flanked by an assortment of talent from the likes of Real Madrid, Atlético Madrid, and Real Sociedad (and possibly Barça’s bench).

The aforementioned core is large enough to preserve key Barcelona synergies that configure the way Spain operate, gifting Vilda’s troupe an unmatched level of in-possession sophistication and variety relative to their competition.

Take this press-resistance sequence:

Patri Guijarro is absolutely nuts, here.

She offers as an outlet for Leila while simultaneously scanning her surroundings, predetermining a flick into Mariona. Before the latter can even return the pass, Patri is already on the move.

This provides an immediate option for Spain to progress out of the congestion on the wing, and it’s important to note that Mariona reads Patri’s intentions instantly.

Guijarro’s precise first touch allows her to open her body to the far side before quickly poking the ball beyond the back-presser. As possession returns to her, she outwits Finland’s final attempt to trap Spain with a first-time switch.

Now, go watch it again.

What you just saw was high-tempo, world-class ball circulation in a high-risk situation. That is only possible when lightning processing speeds and elite technique are governed by a collective understanding of each teammate’s tendencies in relation to implicit tactical fundamentals (i.e. how to dis-mark, offer to the ball, ensure correct body shape, etc.).

Patri and co. bring that level of understanding and quality to whatever sequence they’re a part of, including ones in the final third.

And it is in advanced locations where Aitana really shines.

Bonmatí is a master of movement. Her knowledge of what spaces to attack in any given context meshes beautifully with a preternatural feel for manipulating and fooling defenders. In the above clip, she hides out of sight before quickly dipping in front of Eveliina Summanen. Mariona, as usual, reacts in sync, having been searching for a cute pass into the box all along.

Even though Aitana never has the opportunity to feed the ball back to her provider, Mariona’s relentless associative desire is key, causing her to burst into the area (she sees the faintest chance of getting on the end of a one-two) and drag Finland’s right side with her, leaving Leila in plenty of real estate.

Here’s another clip demonstrating Aitana’s purposeful exploitation of the blind-side:

The off-ball qualities of Barcelona’s interiors have always been their most underrated characteristic; time and again, Aitana split the last line to get onto lofted deliveries, eventually leading to the go-ahead goal.

It’s obvious that Mapi is searching for these runs and is primed to pull the trigger as soon as she sees a small flash of red barreling towards the net, endowing Spain with an additional weapon to break down deep blocks.

Expanding Synergies

The challenge, then, is to expand these synergies to include those outside the Blaugrana circle. As it stands, the unfamiliarity of Spain’s attackers with the near-reflexive connections of the Barça crowd limits the ceiling of Vilda’s crop. Spain are essentially in a race against time to acclimatize figures like Esther González and Lucía García before the knockout stages arrive.

Esther, in particular, struggles with knowing when to drop and offer to the ball, as her decision-making in this respect is already a weakness in her game. Although the Blancas forward tends to restrict the volume of her descents on the international scene, the whizzing pieces around her can coax her off the last line; Esther sees a more dynamic game being played in regard to movement and wants to be a part of it. That’s all well and good, but she needs to be more aware of how her involvement relates to those around her.

Notwithstanding the fact that Lucía has handled this better to a certain degree, it’s apparent that she can fall prey to an overwhelming sense of urgency.

Against Finland, she tried a number of difficult actions off-the-dribble in an attempt to stamp her mark on the game. Some of them came off and accelerated the tempo in helpful fashion; other times, her ideas were completely out of place. Modulating these individual urges so that they serve the bigger picture is far from easy and will be a serious test of Lucía’s conception of the team context.

Vilda can help by reviewing these things on film and trying to key Esther and Lucía into specific cues (i.e. the movement of one teammate or the amount of support in a given area), but his influence can only extend so far when the brainiacs of his side are constantly inventing things on the fly.

Regardless, that may not be the biggest problem he has to address.

The Case for Utilizing Back Threes in Possession

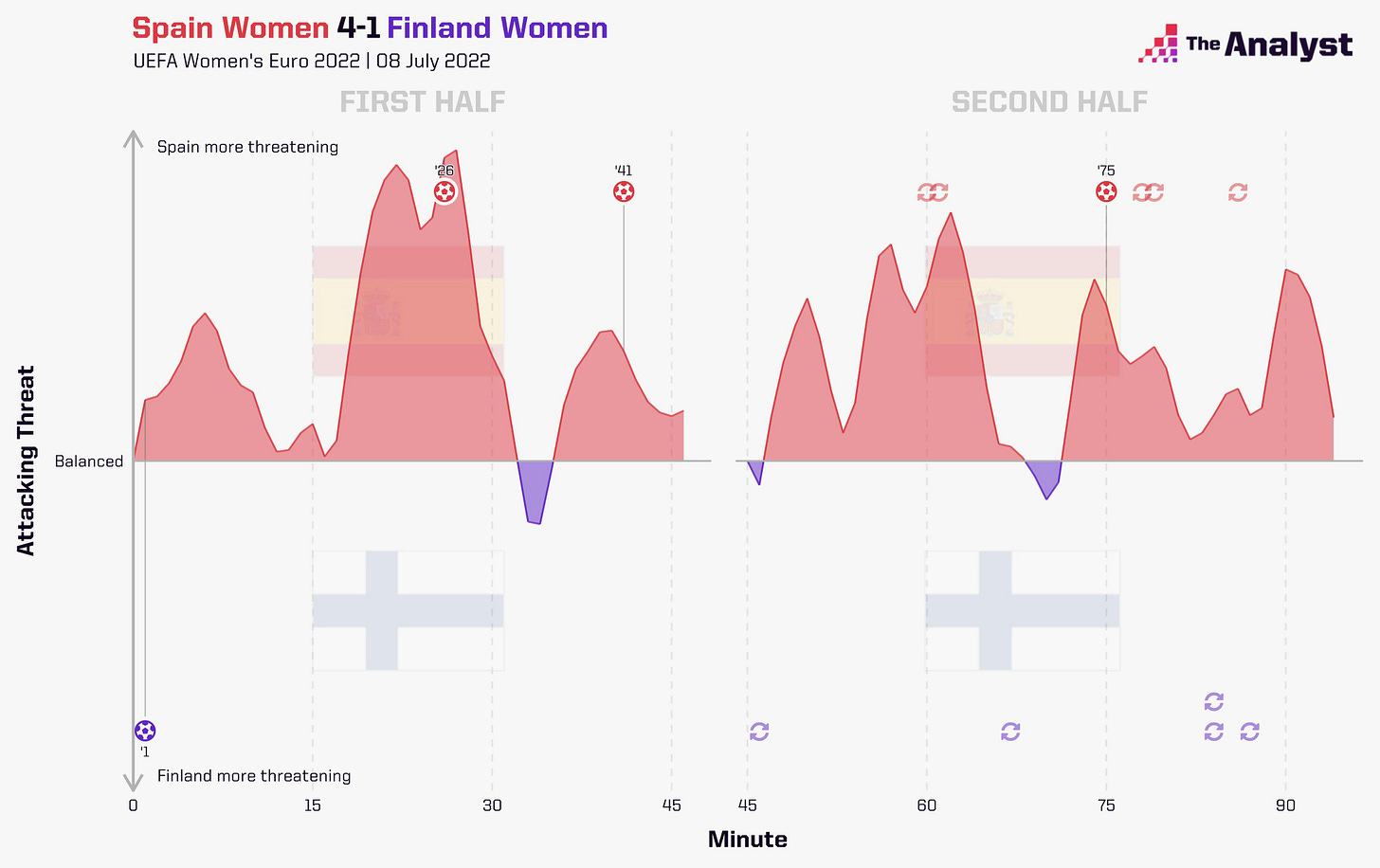

Ultimately, complaining about Spain’s ability to disorganize a defense could reasonably be classified as nitpicking — the 4-1 winners racked up 32 shots and ~3.4 xG vs. Finland.

Rather, their primary attacking issue had to with defense.

Yes, defense.

As we all know, the manner in which a team sets up in possession affects how they defend in the moments directly after they lose the ball, meaning that offensive structure is, in essence, the first stage of defensive structure.

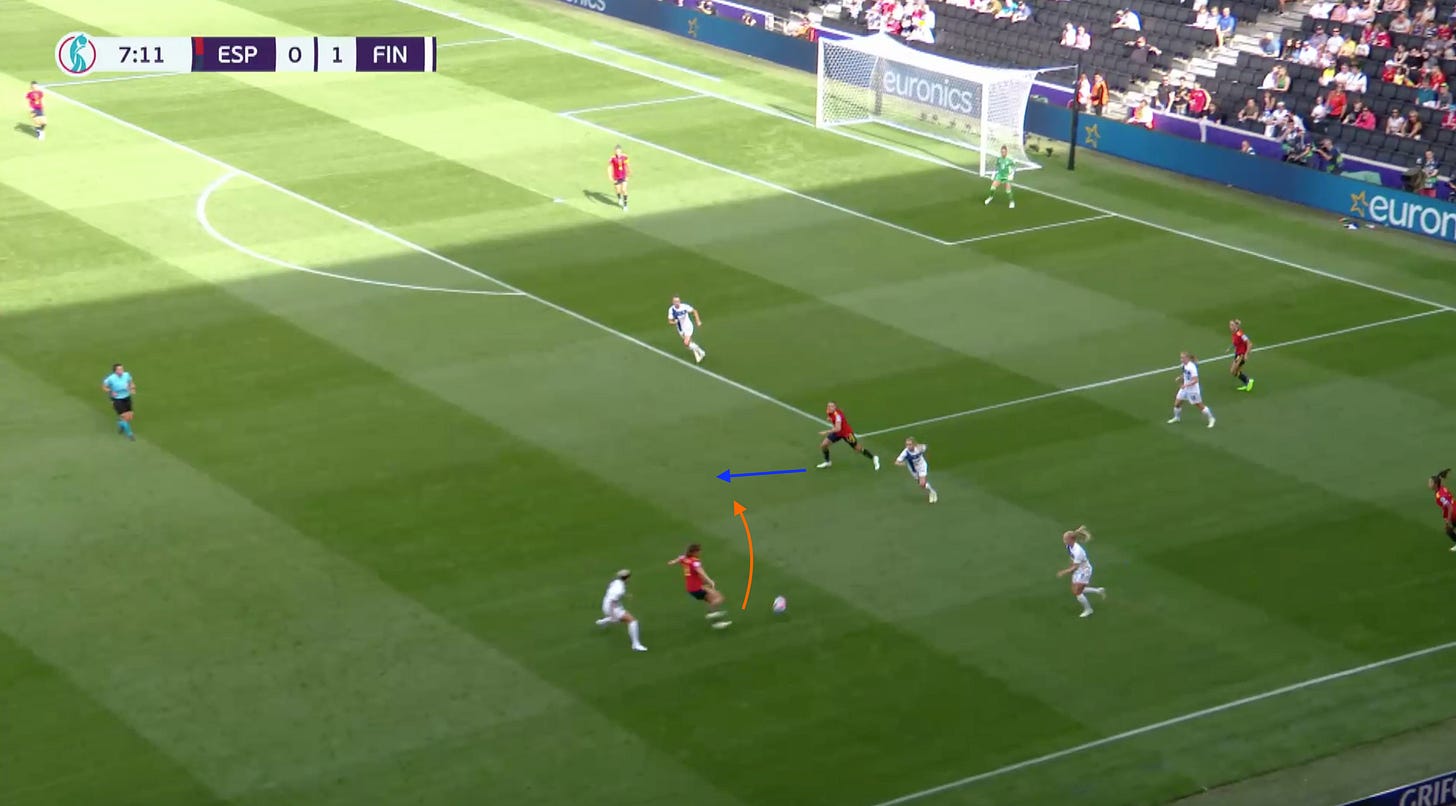

Spain play in a very aggressive and expansive way, throwing both fullbacks forward and deploying a regista ahead of two center-backs. As a result, Mapi and Irene are often the sole figures in positions to stop counter-attacks if the counterpress gets beat. In a lot of instances, Spain get away with it thanks to the individual brilliance of the duo. Nevertheless, in some scenarios, things can get dicey.

A general rule of “rest defense” (offensive structure that prepares for defensive transition) is to have a +1 at the back. If the opposition defends with only one outlet up front, you only need a pair of individuals to deal with them. If they have a front two, you need a trio. Given that Finland often defended in a 4-1-4-1 (Sanni Franssi shifted in and out of the second line), dropping someone deeper might’ve seemed like overkill.

But everything is contextual. The nature of Mapi’s and Irene’s profiles, mixed with the aggressiveness of Spain’s approach, constantly called the two CB’s higher to engage in risky, line-breaking actions. In the above GIF, Paredes isn’t actually in a proper position to deny the run in behind (since she had driven forward to initiate), forcing Mapi to come over and put in a challenge that probably should’ve been deemed a foul. In effect, Spain only had one player covering for one attacker in contravention of the +1 edict.

Building with a back three would’ve put Mapi closer to the ball side and likely would’ve given her the yards she needed to intervene in a way that would’ve been less reliant on a favorable call from the referee.

In this next cut of film, you can see Franssi up alongside Linda Sällström without any adjustment in shape from Spain. Thus, when Mapi gives the ball away, Sällstrom has a completely free lane to attack if the pass could find her; Irene is lurking but would have to cover a large distance before being able to put in a challenge. Even if the ex-PSG star gets there (which she may very well do), her reaction would open up an avenue for Franssi to attack.

The only saving grace for Spain (besides Mapi’s superb interception) might be how quickly and ferociously Ona Batlle and Mariona are tracking back. But sheer effort can’t always beat the physical realities imposed by distance and spacing.

This clip is a perfect example of why the +1 rule exists — you’re playing with fire if you’re relying entirely on a 1v1 duel to save you. Even the best defenders get beat, and Mapi was in this case. Franssi creates a 2v1 on Irene (that quickly becomes a 3v1 thanks to a powerful run from midfield), preventing Paredes from coming out to the flank. Meanwhile, Ona has to recover from what is almost a hopeless position.

Another instance of how the aggression of Spain’s center-backs affects the rest-defense equation:

Look at the bind that Mapi is put in.

It’s a testament to her awareness and reading of the game that she chooses the lesser of two evils and banks on someone else stopping the carrier instead of giving up an entire half of the pitch, but it also speaks to how exposed Spain’s center-backs can be in moments. Only a tactical foul stopped the counter, which is always a final, desperate resort.

In this circumstance, it would’ve been prudent to hold someone back in reserve. Modern coaches love to do this by inverting one of the fullbacks; it allows teams to maintain their numbers in midfield while forming a base for a bunch of dynamic interchanges. If the opportunity presents itself, the previously restricted fullback can unfurl out to the touchline and catch the opponent by surprise.

It takes a special type of player to juggle those duties and Ona Batlle is one of the few built for it, but there’s an argument to be made that the profile ahead of her made this unrealistic. Lucía is a player that likes to operate in the channels and would be misused as someone keeping width. One solution would be to swap out Lucía for Marta Cardona or Athenea del Castillo, who both make a living as 1v1 specialists at the extremes of the pitch.

Alternatively, Vilda could ask Patri to drop between Mapi and Paredes. However, this would moderate her considerable influence going forward.

The final fix would simply be to utilize a back-three formation. The presence of three center-backs would make the shape in the last line more rigid, hence, simplifying questions about who should be cautious and when.

I thought this is what Vilda was trying to do when he brought on Laia Alexandri for Irene Guerrero in the 60th minute, but Spain kept the same shape. While Laia’s minutes as a DM with Spain are well documented, part of the argument for Vilda’s selection of her — when he had already picked four CB’s — in lieu of a true midfielder was that it would give him the flexibility to add another number in defense.

Vilda may very well turn to that in future encounters, but his tactics against Finland proved that the 4-3-3 is very much on the cards. In the event that he does use that same formation again, he needs to implement more back three variations so that Spain can manage counter-attacks without being locked into subbing someone off for a center-back.

As an added bonus, instituting these changes would help address the problems that arose in the Arnold Clark Cup, where Spain struggled vs. England’s intense high press. Despite the genius in the former’s midfield, it became evident that they needed an overload at the back, which Vilda declined to bring into existence.

That strategic flaw only becomes more relevant in the face of an upcoming matchup with Germany, who stomped Denmark with a frenetic high press and deadly movements in behind. If Spain are to have the upper hand, Vilda needs to refine aspects of his side’s possession game in a cohesive, interconnected manner, with the hope that it will reap rewards in build-up, final-third efficiency, and defensive transition.

Additional reading:

Bayern Munich’s Rest Defense and Nullifying the Transitional Threat of Erling Haaland by Jonathan Stoop (for a great explanation and case-study on what rest defense involves)