Pep Guardiola: The Modern Pragmatist

What looks like idealism is really an evolved pragmatism built to dominate the new tactical age.

This article is FREE, but some are not, including all of my content on the UEFA Men’s Champions League and this article on N’Golo Kanté:

Tactical Rant is currently running a 25% discount for a limited period. There is also a student discount available.

The most popular framing of Pep Guardiola presents him as a football romantic, smelted in the furnace of the Cruyffian school and forged in Fútbol Club Barcelona, where sporting success must be underpinned by aesthetic.

Pep certainly seemed to fit that mold to a tee based on his tactics. In 2009, people laughed at the idea that a bunch of diminutive, technically-gifted figures in the center of the park could dominate and, yet, his Barça did.

Thus, Guardiola’s style seemed like a direct rejection of physicality and pragmatism in favor of beauty. To the eyes of many, there was only free-flowing movement, short passing, and lots and lots of possession. It was highly successful football that seemed to meet an even higher artistic purpose.

Pep’s takeover at Bayern and subsequent reworking of Jupp Heynckes’ techniques only bolstered this perception of him. “Why would he mess with something that captured a treble? Because Fraudiola is a romantic, who only believes in operating in one way.” — 15-year-old me

Perhaps there was some of that in young Josep at Barcelona and in the early stages at Bayern. But those who were paying attention started to notice some things counter to that narrative:

The way Bayern played under Pep was different to how Barcelona played under him. For me, Bayern were not as fluent, rhythmic, fresh and completely different as Barcelona were under Pep.

He came very close in his first few months. I remember a game against Manchester City and I was thinking: “this is unbelievable, we have reached this point again.” Nobody could touch the ball and you could almost play music to their rhythm.

But the ongoing development and attempts to minimize risks was too rational for me. They kept on winning and winning after that great start and still got 90 points or so, but it was no longer as beautiful to see.

It was all planned through and through — they suffocated opponents. Things became more static. It was even more impossible to counter-attack against them in their 4-1-4-1. They were very clinical. They would always score.

They were incredibly consistent, but they were no longer entertaining romantics like at Barcelona or during his first six months at Bayern.

I remember a game where Bayern were trailing and he played two strikers up front, I think [Claudio] Pizarro and [Mario] Mandžukić. At Barcelona, he would have rather lost as a protest than play with two big strikers.

Those quotes are from Thomas Tuchel, in case you were interested.

The truth is that Pep Guardiola has a strong conservatism baked into his philosophy. In possession and on-ball structure, he sees tools to establish defensive solidity first and foremost.

If there isn't a sequence of 15 passes first, it's impossible to carry out the transition between defense and attack. Impossible.

If you lose the ball, if they get it off you, then the player who takes it will probably be alone and surrounded by your players, who will then get it back easily or, at the very least, ensure that the rival team can’t maneuver quickly. It's these 15 passes that prevent your rival from making any kind of coordinated transition [emphasis mine].

- Pep Guardiola on his 15-pass rule from the book Pep Confidential

Now, this is less a hard and fast “rule” and more of a guideline that represents Pep’s fundamental outlook; he is terrified of conceding transitions and builds his entire game plan around trying to contain them. In fact, he hates them so much that he’s been one of the most prolific proponents of the tactical foul (no matter much he likes to deny it) — a distinctly cynical strategy.

What differentiates Pep from many others who have tried to control transitions is the way he does so without compromising his attack, having designed a seamless relationship between in and out of possession phases better than maybe any coach in history. In a sense, you can understand Pep’s positional play as an evolved, modern pragmatism that controls transitions without the historic trade-offs associated with such a focus.

Every step of his career has proven this to be true in addition to revealing an obsessive desire to win above all else. This has been especially obvious when he’s been forced to choose between being a dogmatist or making adjustments to get the job done.

You can see this in broader trends, such as in the 2020/21 season, when a congested fixture list signified the rise of Covid-ball and more physical wear and tear. While Bielsa’s Leeds maintained a ridiculous intensity, Pep dialed back the press drastically and made his possession game slower and more rigid.

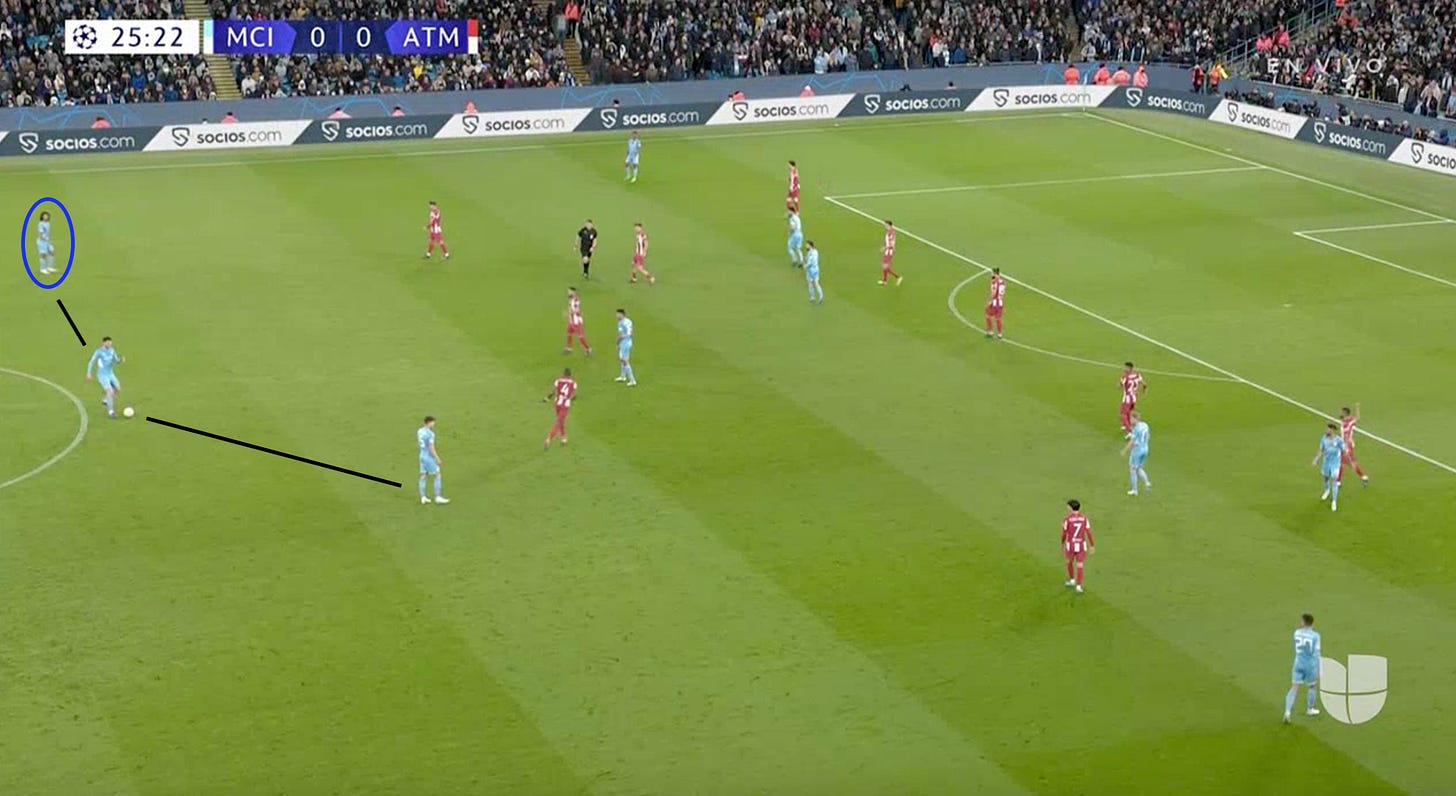

You can also see this in specific games. The recent 1-0 win over Atlético Madrid in the Champions League was a good example. With Simeone asking his team to shrink into a 5-5 deep block, Guardiola continued to keep Nathan Aké (a center-back playing at left back) in a three-man line, despite the overload he offered in build-up being essentially pointless.

Aké stayed put because he was there to stop counter-attacks, however unlikely they were to materialize from such a defensive opponent.

If Simeone doesn’t like to concede goals, the City boss likes to concede goals less:

Pep trusted that his team could grind out the 1-0 victory (which they did), preferring the lower-risk proposal over a higher variance, gung-ho approach1 that might’ve given Atleti one extra chance.

But perhaps no opponent has shed more light on this side of Pep than Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool. In a lot of ways, The Reds can be seen as the antithesis to the Guardiola school of thought. Transitions aren’t to be feared but embraced — a wild animal that should be unleashed to bolster offense instead of tamed in order to protect defense.2

In the budding stages of their rivalry, this made Liverpool Pep’s worst nightmare. A 4-3 win in the 2017/18 Premier League season, followed by a 3-0 demolition in the Champions League, were powered by a mid-high, 4-3-3 block that turned City’s desire to build through the center against them.

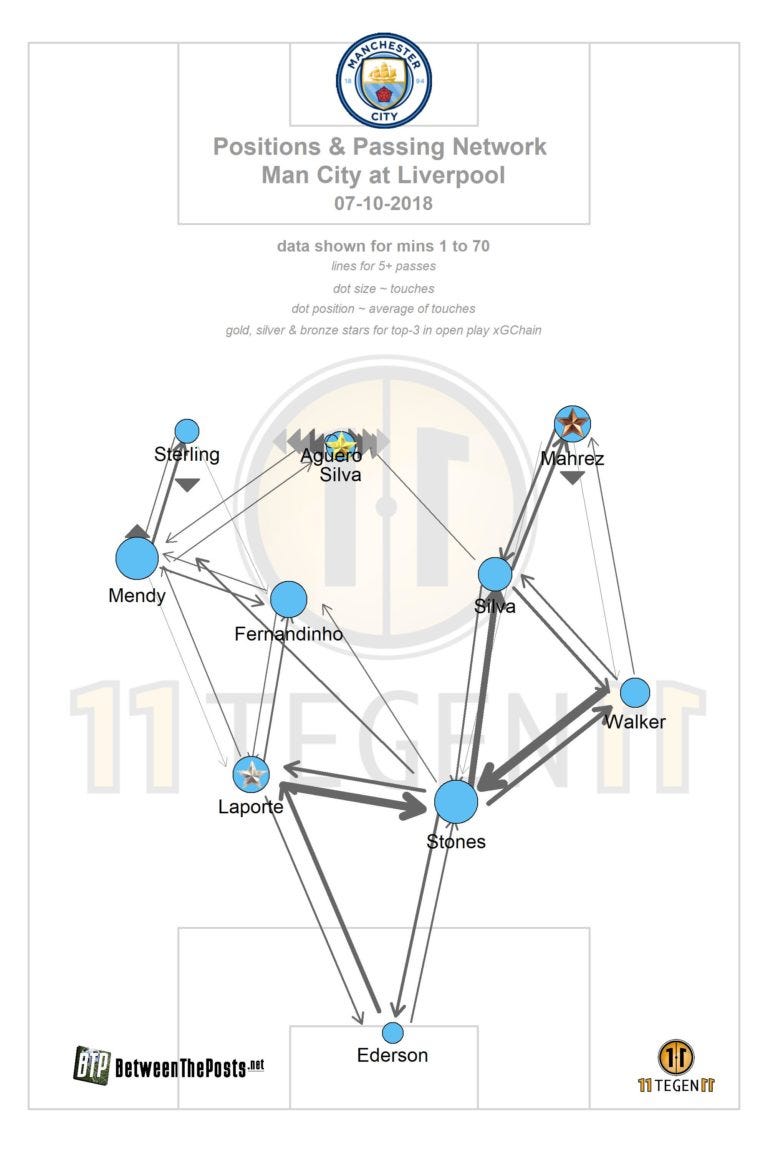

In the next round of matchups, Pep responded by rejecting the middle and building cautiously through the wings, birthing pass maps that looked completely unlike the sides he had always constructed.

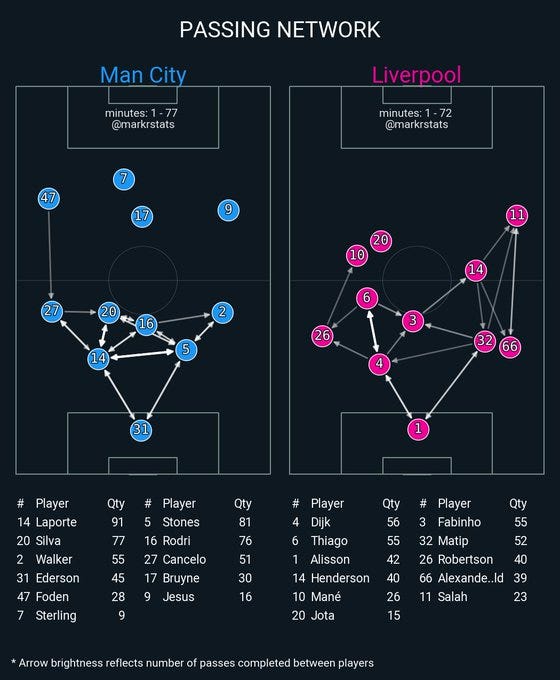

Yesterday, against the same opponent, we witnessed a different strategy but a similar, pragmatic spirit. Instead of progressing down the touchline, Pep instructed his team to go long. A lot.

One feels compelled to argue that the line of code that created these passing networks glitched out, but these patterns (or lack thereof) are reflected in heat maps, touch ratios, and the “eye-test” (and other passing networks).

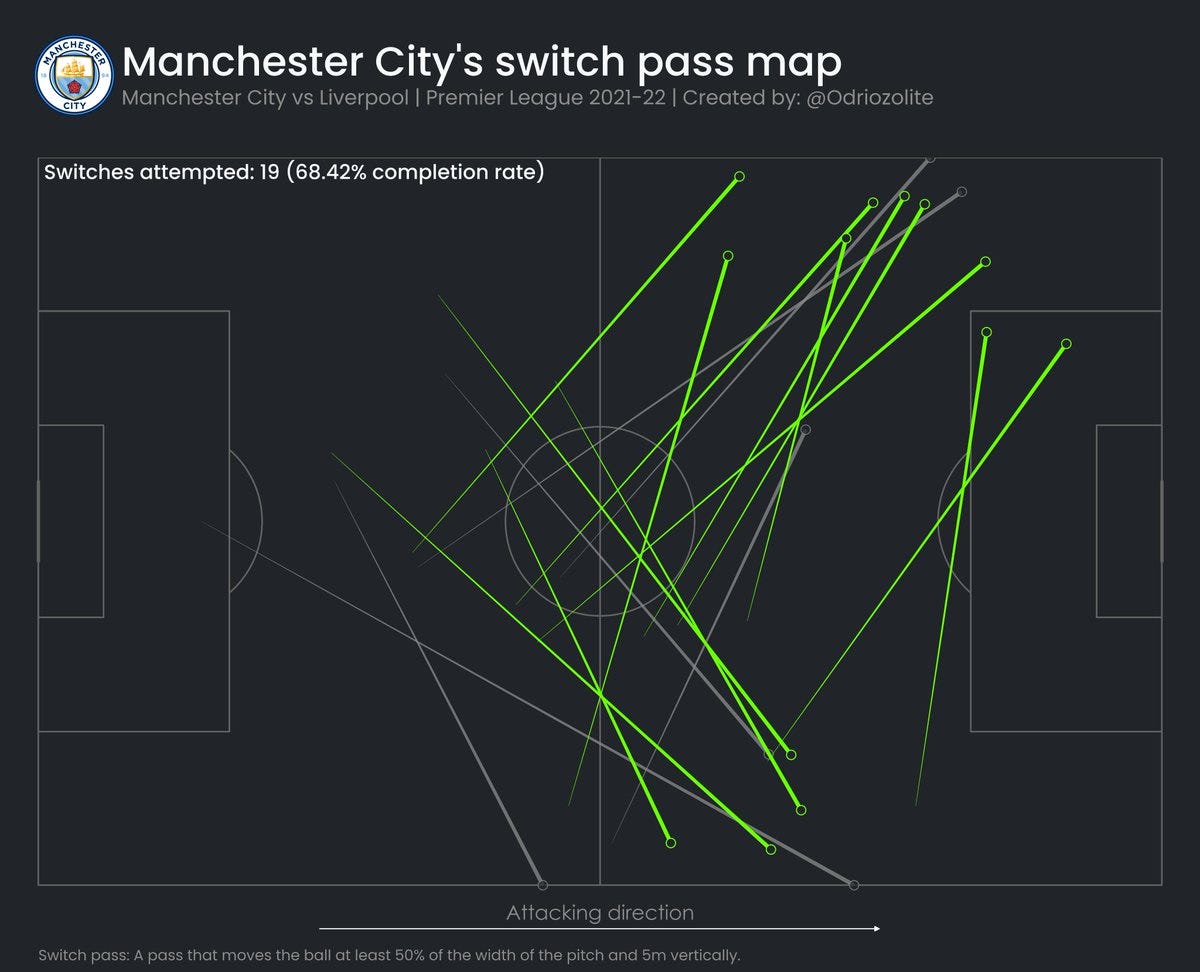

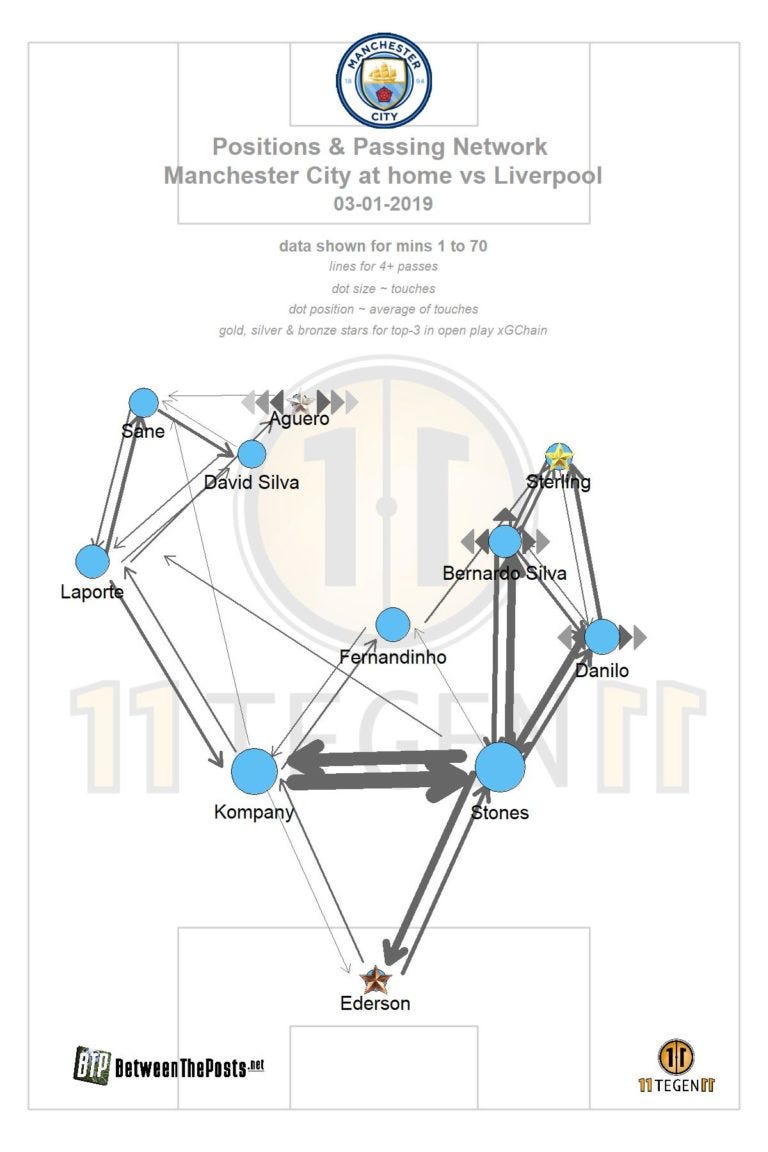

Facing a typically narrow mid-high block, City passed the ball to death at the back, using a double pivot overload of Bernardo Silva and Rodri to retain possession safely. Then, when someone shifted a yard out of position, such as a winger cheating too far inwards, City funneled the ball out wide — often through big switches — and looked to hit the channel.

Sometimes, The Sky Blues simply went straight over the top from Laporte, Stones, or Ederson [25 attempted long balls between them].

Meanwhile, De Bruyne floated ahead as a free #10, alternating between offering support between the lines and making runs off-the-shoulder. There were no interiors and little to no intricate passing through the block.

To put it simply: Manchester City played like they never had before while retaining a distinct Pep feel to it all.

City still had the patented, deep overloads and still sought to use them as a base to launch attacks. Additionally, the selection of Gabriel Jesus — although serving as pre-match fodder for how Baldiola had overthought things once again — was vintage Pep. The 51-year-old has enjoyed using strikers as false wingers since the Henry-Eto’o days at Barcelona. Versus Liverpool, Jesus’ positioning and movement added numbers against the last line, helping to pin and occupy defenders to create space for runs in behind.

City’s tactics on Sunday were Pepian at its core — just modified to meet the needs of a potentially title-deciding encounter. Cognizant of Liverpool’s defensive dominance through the middle via their pressing traps, Guardiola found a way to bypass the midfield through a long ball approach, making it viable as a high-percentage strategy by virtue of clever structure and team selection. In the process, he was also able to target a supposed “weak link” in Trent-Alexander Arnold.

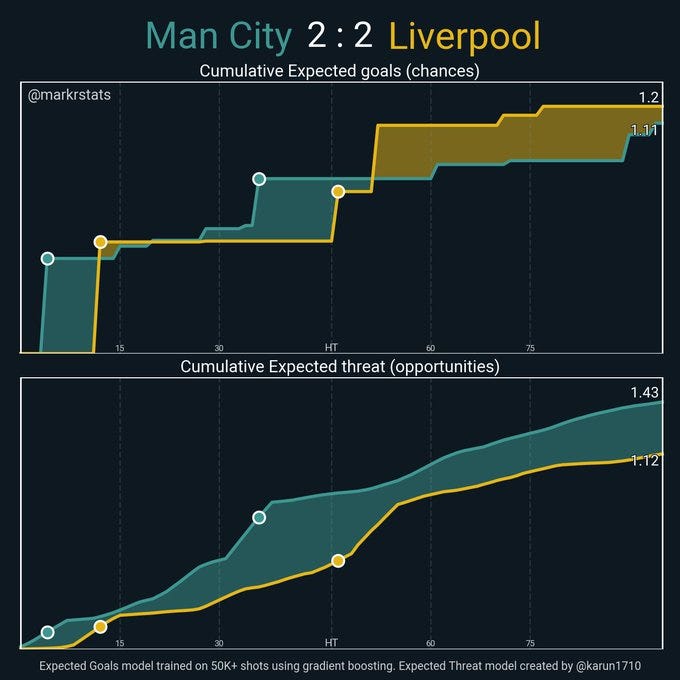

It worked. City were the vastly better side for the entire first half and continued to enter the final third in the second through a similar manner. But Liverpool struck at crucial moments and tightened up their execution coming out of the tunnel, causing the match to end in a 2-2 draw. Liverpool and Klopp are good, too, it turns out.

On Saturday, Manchester City and their rivals in red will do it all over again. It is certain that there will be talk about what wild scheme Pep comes up with next, implying that he over-tinkers and tries to be too clever. And, you know what? Who knows? Maybe he does pull a 2021 Champions League final and tries to pay homage to Cruyff with a 3-4-3 diamond. But don’t bet on it. That version of Pep, however compelling and part of his identity it might be, is most often subsumed by a ruthless desire to win, whatever that may require.

One need only look at the tenets of his footballing philosophy and the way it has morphed and manifested vs. his greatest rival for evidence of this.

Aké — or a sub — could’ve bombed on with Sterling inverting, creating front six looks or more interchanges into and out of an attacking group of five.

It’s a little bit more complicated than that. Although this was very much Klopp’s view in the earlier stages of his career, Liverpool have gradually shifted to a style that emphasizes greater control — best signified by the signing of Thiago. At the highest of levels, even Klopp has had to concede that suppressing variance is essential. Nevertheless, Liverpool still operate at a significantly quicker pace and under very different tactical directives than City.