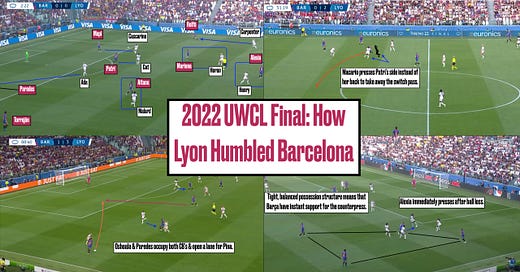

Dissecting the 2022 UWCL Final: How Lyon Humbled Barcelona

Sonia Bompastor found a weakness and the eight-time champs exploited it.

This article is FREE, but some are not, including all of my content on the UEFA Men’s Champions League. Tactical Rant is currently running a 25% discount until May 28.

There is also a student discount available.

NOTE: If the videos do not work for you, click the embedded tweet and they should play on Twitter.

In my tactical breakdown of Real Madrid’s electric performance in the 1st leg of the Champions League quarter-finals, I opened with the question: “how do you approach FC Barcelona?”

As a sort of answer, I lauded the way an aggressive, high-pressing scheme could throw Barça off their rhythm and generate turnovers, all while considering the defensive value of a patient mindset in possession. The way I saw it, denying the Catalan outfit entry into the final third — both with and without the ball — was critical to any chances of success.

But the truth is that there is no foolproof way to approach one of the most dominant forces in football history. A high press might prevent a greater volume of final-third entries, but it could concede a greater number of dangerous ones. In a similar vein, patience in possession might ensure relief from Barça’s suffocating rest defense1, but it could lead to unexploited offensive windows, turnovers close to your own goal, and a game pace that suits La Blaugrana.

On the flip side, anything conservative and direct could result in an endless, dispiriting cycle — Barcelona attack → Barcelona turnover → Barcelona possession regain → Barcelona attack — that punishes your lack of ambition by dooming you to a slower but surer death.

Picking the right plan to face Barça isn’t so much about choosing the one that exposes all their weaknesses — it’s about deciding which tradeoffs are worth it and which aren’t based on the capabilities of your squad and how they relate to the opposition’s. Then, it requires actually executing at a high enough level so that the rewards outweigh the risks.

This necessary confluence of factors naturally limits the pool of contenders that even have a shot at coming away with a result; not only do you need a coach smart enough to select, design, and train the correct strategy, but also a host of world-class players to bring that vision to life.

Luckily, for Olympique Lyonnais, they had both of those things (and more) coming into the 2022 UEFA Women’s Champions League final against the defending champs.

Lyon Choose Bravery

Any queries on what poison Sonia Bompastor would pick were answered within literal seconds.

Lyon brought it from the off and injected a frenetic energy into midfield that was exemplified by Lindsey Horan’s sliding challenge on Aitana Bonmatí at the end of the GIF.

The objective was to aggressively contest any pass into midfield through a player-to-player structure that was colored by an orientation to the ball side. Delphine Cascarino would park herself next to Mapi León, while Ada Hegerberg completed the front two and Catarina Macario sat on defensive midfielder Patri Guijarro.

As Barcelona built down their preferred left-hand side, Ellie Carpenter (it was Mbock after Carpenter got injured, with Kadeisha Buchanan coming on at center-back) would step up to Fridolina Rolfö.

Lyon denied the Swede any option back to the middle by parking Horan on the dropping Mariona Caldentey — who is more of a central playmaker than a winger — Amandine Henry on Alexia Putellas, and Melvine Malard on Aitana. This left Marta Torrejón as the nominal free player.

If it helps, you can visualize Lyon’s structure as a diamond situated behind a front two, with a very aggressive right back trying to dispossess Rolfö.2

This was a sharp and straightforward way of congesting the areas Barcelona liked to operate in and also addressed the interchanges between Mariona and Alexia, which have been a fundamental method to generate overloads and discombobulate defensive structures over the years. There were no questions about who would take who if one dropped and the other roamed ahead — it was Horan on Mariona and Henry on Alexia.3

Any trading of assignments occurred whenever Barcelona shifted the point of attack to the right, which can be seen in the second clip; Lyon would simply reset into a similar ball-sided structure, with Malard going out to Torrejón, Henry rotating to Aitana, and Horan cutting out balls into Alexia.

The clarity of Bompastor’s system allowed for seamless coordination in midfield and empowered her personnel to fully commit to winning their individual duels. Her players took advantage by displaying an immense work ethic and a remarkable attention to detail.

For example, in the below play, Macario curves her run to prevent Barcelona from breaking out of the congestion, placing herself side-by-side with Patri instead of arriving from behind. Cat was less worried about the defensive midfielder getting free on the turn and more preoccupied with the Spaniard’s preference for the one-touch switch pass.

The result was a high-octane opening five to six minutes and a number of high turnovers for Lyon.

The Torture of Playing Barcelona

In the 6th minute, Amandine Henry saved a poor Hegerberg pass by toppling Alexia with a sliding challenge. The 32-year-old vet quickly found her feet, looked up, and pummeled a thunderbastard past Sandra Paños.

It was one of those brilliant and random game-changing moments that is impossible to plan for, seemingly putting Lyon in prime position to dominate the game.

However, all it took was one Barça progression into the final third to flip the dynamic that had reigned so far. In the 8th minute, Mariona pulled too wide and deep for Horan to follow and Barcelona made it into the opposition half.

And that was it. For the next ~fifteen minutes, Lyon were pinned back so deep that their vaunted press became a non-factor.

This is the true torture of playing Barcelona. Despite some superb defending from the likes of Malard (back-pressing on the first clip) and Renard (stepping out of her line in the second clip), Lyon couldn’t buy an ounce of relief. The Culés’ sophisticated on-ball structure translated to vicious counterpressing and allowed them to launch wave after wave of attack. There was simply no room for Lyon to work with in tight spaces. To make matters worse, any ball into or past the defensive line was dealt with by Paredes or tracked diligently by a fullback.

It is perhaps for this reason that Bompastor instructed her side to go long from goal kicks. Why not play over the press if you can’t play through it?

Unfortunately for her, that didn’t really work. In fact, Christiane Endler’s goal kicks proved to be more useful for her opponents than Lyon, as they directly contributed to Barcelona’s two best chances of the half, and repeatedly gave possession directly back to their rivals. The only hint of success came from a pass directed at Horan (more on this later) near halftime.

If it wasn’t for a jaw-dropping intervention from Selma Bacha in the 15th minute, Jenni Hermoso would’ve equalized from one of these sequences, demonstrating the fine margins that can swing football matches.

The only times Lyon broke free came from sloppy Barça turnovers or rare spells where Barcelona were resetting and their French counterparts had a chance to build out from the back. In the 19th minute, a stray vertical pass spawned a counter-attack and a volleyed shot from Ada. In the 22nd minute, Mariona coughed up possession in a miscalculated attempt to find Alexia and Lyon burst away, winning a throw-in deep in enemy territory. The following cross to Horan was collected by Cascarino, sparking Lyon’s first organized attacking stint in the opposition half since Barça’s onslaught.

If Barcelona had shown the value of what one progression could lead to in terms of generating attacking volume, Lyon demonstrated its value by producing offensive efficiency.

A one-two between Malard and Bacha left Caroline Graham Hansen in the dust and some questionable defending from Mapi helped Ada get free for the score.

This was the moment when Barcelona began to crack. Their total control over proceedings subsided and, ten minutes later, a comedy of errors ensued on a Lyon high press, blessing Giráldez’s side with a three-goal deficit.

Yet, Barça’s threat remained omnipresent and, in the 41st minute, Lyon got complacent and fell asleep.

It says a lot about what it takes to stop Barça when this was probably Lyon’s first real breakdown of the match.

What Barcelona Could’ve Done Differently

It’s tempting to fall into the trap of assuming that this game was simply about the moments and that Barcelona would’ve won had things gone slightly differently. There is an element of truth to this. Henry’s goal was incredibly low percentage and Barcelona responded with dominant football that could’ve easily leveled the bout, but this presumptuous narrative brushes over the flaws within La Blaugrana’s game plan and Lyon’s initial tactical superiority.

Bompastor read Giráldez’s lineup selection and preferred dynamics perfectly. Her decision to use Carpenter/Mbock as a presser while keeping Bacha back was no accident. Rather, it was a specific reaction to the two sides of Barcelona’s structure.

As mentioned before, Mariona is less of a winger and more of an extra midfielder. Her value is derived from ball-dominant, free-moving tendencies in central areas. Jenni provides impact in a similar way from the center forward position, although dropping off to receive to feet was not an issue with her on the day. Instead, she didn’t provide the necessary mobility to occupy various parts of the back line and possessed muted off-ball gravity (due to a lack of of pace).

Consequently, Lyon didn’t respect whatever threat Barcelona could muster in the left channel and felt safe throwing their right back forward.

On the other side, the best winger in the world, Caroline Graham Hansen, stayed high and wide. If Bacha was the fullback who stepped up (with Mbock taking a CB alongside Ada and Cascarino tucking in on a central midfielder), the much slower Renard would’ve been left on an island vs. a 1v1 monster.

By setting her press up the way she did, Bompastor exploited the redundancies on Barça’s left and neutralized the threat on Barça’s right. Of course, her tactics only worked because of the individual execution:

The easiest solution to this would’ve been to start Asisat Oshoala. Despite ending the season tied in the Pichichi race with Geyse Ferreira, the Nigerian has repeatedly been lambasted for her finishing. Oshoala admittedly does have some issues with her body shape when striking the ball, particularly in 1v1’s, but this flaw has wrongly overshadowed her lethal off-ball game for far too long.

Unlike Jenni, Oshoala has a level of positional discipline that can’t be weakened by a desire to get touches.4 When mixed with her high motor, particularly on the left-hand side, Oshoala constantly keeps back lines in check, fixing defenders in place and opening space for Barça’s technicians to do their thing. Additionally, her tactical tendencies are enhanced by her blinding pace and the timing of her runs, which provide opponents with a real reason to fear her movement and a high motivation to stay with her at all times (i.e. off-ball gravity).

This type of profile is the perfect match for Mariona’s contrasting tendencies and had been a staple dynamic of Barcelona’s attack until injuries complicated the picture. Perhaps Oshoala’s relatively recent return to fitness dissuaded Giráldez from picking what has always shredded presses and aggressive fullbacks in the past [see: Arsenal], but it proved to be the wrong call.

Jonatan admitted as much when he made the sub at halftime, although it would prove to be too late.

Asisat Oshoala’s Impact

Oshoala was a live wire coming out of the tunnel, pressing with a real sense of urgency and fomenting general chaos in the box.

But it was that off-ball movement that held the greatest potential for Barca.

All of a sudden, there was a lot more uncertainty introduced into Lyon’s method of defending Barça’s left-sided combinations. Mbock constantly feared the space she was creating as she closed down Rolfö, and Buchanan had to constantly hedge against activity in behind. On a few occasions, it looked like Barcelona were going to completely carve the scoreline leaders apart, but either the pass didn’t arrive or came too late.

This type of manipulation of a back four is why I’ve sometimes argued that an extra defender is necessary when trying to defend Barça. Their wide threats demand the sort of non-negotiable attention that will open up exploitable spaces in the channels if there is only one center-back to cover. However, that is only really the case when Oshoala is in the team. If she’s replaced by anyone else, high-level opponents can bank on skilled defenders to contain slower or later-arriving individuals while sending troops to the wings.

This final is a lesson in what offensive impact actually entails for a center forward. It’s not just about what you do with the ball and how much you score (or the rate at which you finish) — it also has to do with off-ball movement and tactical fit and the possibilities that such attributes can unlock for your team.

That being said, Barcelona didn’t exactly kick off the second half as the better team. In fact, they actually lost control of affairs for a period while Lyon managed 3 shots inside the first ten minutes compared to Barça’s 0.

Lyon Adjust Their Long-Ball Strategy

Lyon’s fast start to the second period was reminiscent of their blitzkrieg in the first, but arose from a fundamentally different reason. With Oshoala in the side and a quarter of an hour for Jonatan to convey ideas to his team, Bompastor’s pressing blueprint became less of a weapon, although duel-winning remained a focus.5

Instead, most of Lyon’s early success at sustaining some offensive pressure emerged from a slight adjustment in their long ball game.

If you remember, Lyon went long quite a bit over the first forty-five minutes and experienced generally poor results. In that stretch, Endler picked out a variety of targets at a variety of heights. Bompastor tweaked that at the break, designating Horan as the focal point behind Ada, who fought to receive flick-ons from the American.

Although Horan’s physicality, height, and combativeness yielded good returns in at least three long-ball sequences (there’s possibly a fourth in the 74th minute), the benefits began to fade as Barça caught on.

Even when Lyon had won the first few duels in midfield, the fifty-fifty nature of the ploy gave Barcelona chances to claw back possession and launch attacks against a potentially unset defense. After a certain point, one had to wonder whether fomenting an end-to-end atmosphere was a beneficial dynamic for a side that needed to protect a lead.

Nevertheless, it worked in the opening phases of the half, stalling Barça’s ability to reimpose themselves.

And, at this juncture, burning time was a huge win for Lyon, which is why they probably started wasting it as the match drew closer to the final whistle (notwithstanding the fact that their antics were not quite as extreme as Culés would like to imagine).

Jonatan Giráldez’s Hail Mary

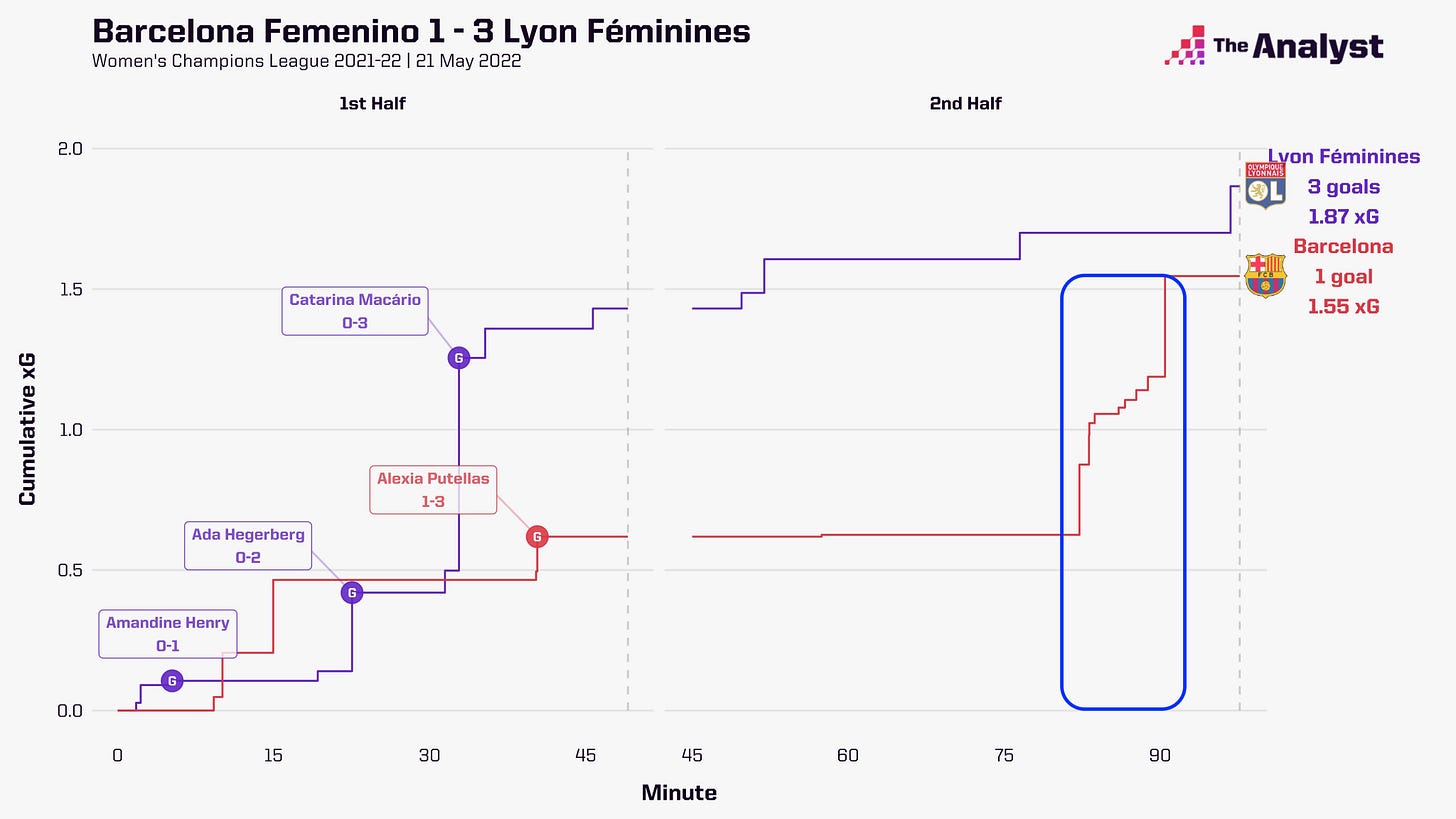

The Oshoala sub was supplemented by the introductions of Lieke Martens and Ana-María Crnogorčević for Mariona and Torrejón, respectively, in the 59th minute. This didn’t have the desired outcome and Claudia Pina soon came on for Rolfö, pushing Patri into defense to fashion a vague 3-4-3 look (Pina operated as a free attacking midfielder). Yet, it wasn’t until Irene Paredes became a permanent center-forward around the ~80th minute, that Barcelona began to generate actual shots.

The desperate gambit completely overloaded Lyon’s back line; there wasn’t much the French side could do to stem the onslaught despite the arrival of defensive reinforcements like Perle Morroni.

But Lyon held on and, eventually, the final whistle sounded.

What Should We Take From This?

The beauty of finals between teams from different leagues is that you only get to see them play once. Whatever happens, happens. There is little recourse to rectify any mistake or incorrect tactical decision, thereby raising the stakes and creating a suffocating tension that permeates throughout the entire event.

It also makes finals like these uniquely difficult to analyze. There are innumerable factors to consider without the benefit of a significant sample size, meaning that, at the end of the day, conclusions must be tentative.

Had Oshoala started, would Lyon’s press, which set the table for a superior Lyon start, have looked nearly as good? If Amandine Henry didn’t score the goal of the tournament, would Barcelona have scored first?

These are legitimate questions, but they should not detract from the fact that Sonia Bompastor mostly chose the right tactical setup for the Barcelona that appeared on the day. Her press exploited the deficiencies of a not-uncommon pairing and directly resulted in a goal. While Lyon’s long-ball strategy flopped in the first half, Bompastor adjusted it just enough to give it brief viability, demonstrating admirable game management, which bled over into cynical but pragmatic time wasting.

But, most importantly, Lyon’s players showed up and performed in a manner that Barcelona’s did not.

Bacha put on a display for the ages, locking up the best winger in the world and providing a gorgeous assist on the other end.

Mbock starred in the center of defense before deputizing at right back without a hitch.

Wendie Renard was masterful positionally and stepped out of her defensive line to cut out danger time and time again.

Catarina Macario had muted offensive influence despite her goal but put in an immense shift against the ball, back-pressing like a maniac and doubling up on Alexia.

I could go on. Each and every Lyon player executed at an exceptional level, enabling them to both realize Bompastor’s vision and help Lyon tread water in the difficult moments.

So, could Barcelona have won had things gone differently? Sure (which is important to keep in mind when evaluating overall team strength), but the fact is that things didn’t go differently and Barcelona didn’t win — in that reality, Lyon were the better team.

Additional Reading:

This refers to a team’s defensive structure when they have the ball, specifically in the moments directly preceding a turnover. In “juego de posición” (as the Spaniards would call it), it is particularly important for there to be a seamless transition between in-possession and out-of-possession phases, since football operates on a continuum — rather than distinct junctures — between offense and defense. Thus, the attacking shape will be designed so that players have to reorganize as little as possible when the time comes to counterpress.

This is quite different from what Real Madrid did recently, which was a flat 4-4-2, with the front two having to control the two center-backs and Patri. However, Las Blancas did try a diamond press vs. Barça under David Aznar in the 2020/21 season. Of course, I wrote about it.

Needless to say, there were times when the marking looked different thanks to the natural flow of the game. Sometimes, players would be reorganizing into shape from random positions and had to take who was closest to them or adjust to someone else not getting back in time.

I have been talking about the different tactical contexts that Jenni and Oshoala foster since last season.

Case in point: one of Lyon’s best attempts of the half (a Cascarino volley over the bar) came from a flick-on off of a throw-in.

Fantastic piece! I really enjoyed the game and your rant made me enjoy it all over again. I will go back and watch the first half to Barcelona's dominance you describe. I think I forgot that phase at the end.