Tactical Theory: How the USWNT Could've Defeated Sweden

It all comes down to the movement of the pivot/s.

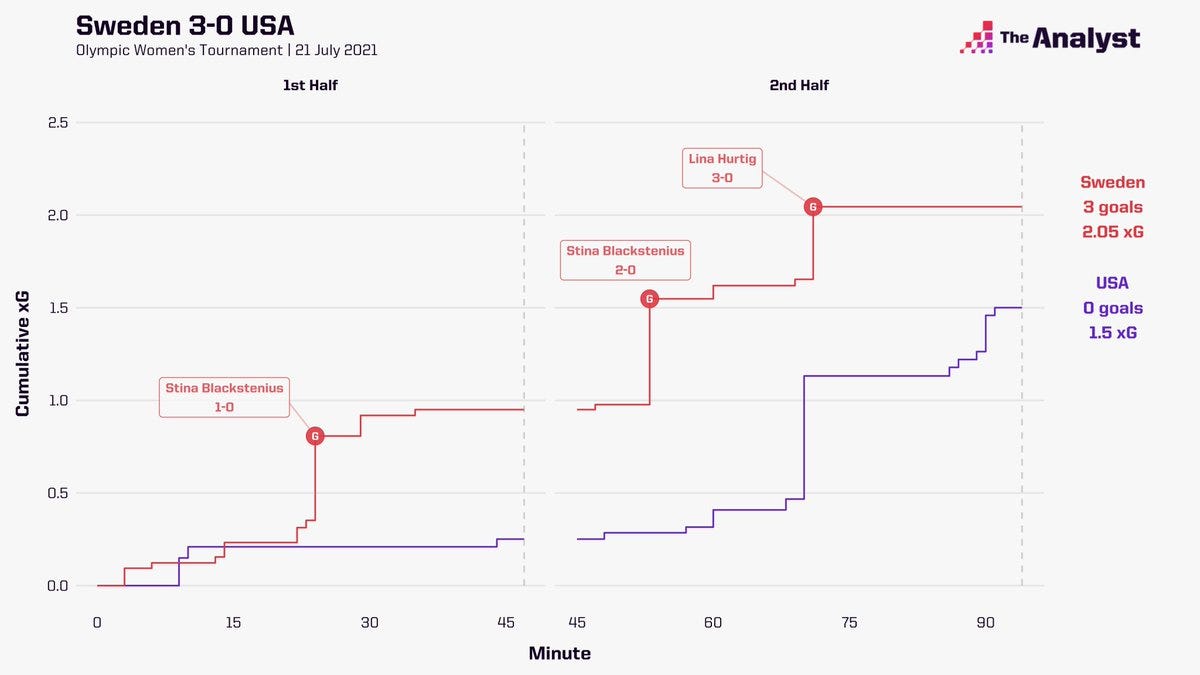

The USWNT’s 44-game win streak is over. Sweden thrashed the best team in the world 3-0 in a scoreline that somehow might’ve been flattering to the losers if we counted non-shot xG in the first half. Even when just looking at attempts taken, the result was indisputable.

Megan Rapinoe was blunt in her assessment of her side’s performance: “We got our asses kicked, didn’t we? I thought we were a little tight, a little nervous, just doing dumb stuff.”

That was certainly part of it — a sense that none of the individuals showed up and, instead, combined to put on an uncharacteristically lethargic, mistake-laden showing. But that was, in part, engendered by Sweden’s own play.

The Crux of the Problem

Sweden were victorious thanks to their spectacular defense. Peter Gerhardsson’s move to a 4-4-2/4-2-3-1 after trialing a back three in prior games may have caught the US by surprise, but Sweden’s organization and cohesion were reflective of an identity that has caused problems for the Americans historically.

In Round 1 of the Olympics, Sweden focused their strategy against their opponent’s 4-3-3 by denying passes into the single pivot: Lindsey Horan. Kosovare Asllani was primarily responsible for this and would sit on the defensive midfielder to create a 4-4-1-1 structure that left Becky Sauerbrunn free — at least initially.

As Sauerbrunn waited for options to emerge or carried the ball forward, Asllani would step out to press the center-back while blocking off the passing lane to Horan, creating a vicious sideline trap that squeezed the USWNT and forced turnovers.

Asllani was simply brilliant on the day, managing her double assignment with intelligence and a high motor, shifting back onto Horan as necessary and resetting to press Sauerbrunn. Her teammates worked in unison to keep the structure compact; Jakobsson would press in a way that denied a pass back into the center and Filippa Angeldal would step up to Horan to buy time for Asllani to recover, if need be.

The ability to react on the fly in order to maintain tactical integrity is a telltale sign of advanced chemistry and is what makes a good defensive team great. Beyond revealing an understanding of each’s individual role, it signifies a larger appreciation for the collective purpose, which (when combined with elite mental processing speeds) allows for the spirit — and not just the instructions — of the coach’s vision to manifest on the pitch.

Though there are other parts of that vision worth discussing, such as the 2v1’s Jakobsson and Hanna Glas constantly created vs. Crystal Dunn, Sweden’s ability to shut down Horan and keep their opponent pinned to the wing proved to be the primary obstacle to the US’s success.

Vlatko Andonovski’s & the USWNT’s Adjustments

Sam Mewis Dropping

Sweden’s comfort adapting to various situations in order to execute their defensive style became even clearer when the US started to make adjustments. The first occurred when Sam Mewis began to move deeper, starting around the 25th minute.

As you can see in the first clip, it worked. Angeldal was uncertain about following Mewis too far, allowing the North Carolina Courage midfielder to turn and initiate a combination with Christen Press. It produced a great box entry and an ok chance, representing the first time that the USWNT had broken Sweden’s 4-4-1-1 block (aside from an earlier moment when Dunn simply beat Jakobsson 1v1 and advanced play single-handedly).

That was also the last time this happened.

Angeldal immediately began to track Mewis relentlessly, preventing the American from facing play after receiving. The US reacted by using Mewis to play a wall pass into Horan, except Stina Blackstenius read it and closed Lindsey down.

Sweden were even comfortable exchanging assignments — i.e. Asllani stepping to Mewis and Blackstenius coming to Horan — and never lost pressing access to Sauerbrunn in the process.

In other words, Gerhardsson’s women snuffed out theoretically sound adjustments with elite defensive recognition and coordination. Forty-five minutes in, it became painfully obvious that basic, textbook movements and patterns within the same structure simply weren’t going to cut it against a side this good.

Horan’s & Carli Lloyd’s Deep Movements

My sleep-deprived brain was convinced that Andonovski had gone to a double pivot in the second half when he removed Mewis for Julie Ertz. Perhaps this incorrect observation was partially influenced by a halftime conversation that I had with Reyes (@_EnFemenino) on how the double pivot was a possible solution for the US (more on that later), meaning that I got over-excited and saw what I wanted to see in the moment (a more common and dangerous problem than many analysts will admit).

Upon film review (and a couple hours of sleep) and further clarification from Reyes, I quickly realized that I was wrong. Nevertheless, there did appear to be something different about the US’s look in possession.

This is where the analysis gets tricky. Sweden scored their second from a set-piece in the 54th minute and game state became a massive factor. Whether produced by the USWNT’s desperation or Sweden’s slight relaxation on defense (or both), the match entered a far more transitional state and the amount of dissect-able possessions against a set block dried up.

Below are a couple sequences that I think are reflective of some differences in approach from the US, but beware the small sample size.

In the initial clip, Horan drops quite deep, forming a situational double pivot to combine with Ertz and propel the substitute forward. With Caroline Seger concerned by the potential line-breaking action and also occupied by Rose Lavelle, Carli Lloyd was able to drop into space between the lines to receive.

A similar thing happens in the following play, with center-back Nathalie Björn needing to come far off her line to track Lloyd, who had room to deliver the wall pass as Lavelle and Horan occupied Seger and Angeldal. However, Sweden successfully reorganized even as Horan dropped and replicated the same sideline trap that worked so well early in the first half.

These examples are not a lot to work with, but finding new solutions necessarily involves a certain degree of imagination. We will never truly know if a suggestion will work unless we see it on the pitch vs. the same opponent. Unfortunately, coaches don’t often have the luxury of using competitive games as test runs, which is why rigorous thought exercises are sometimes the best alternative.

Thus, let’s dabble in some tactical theory.

Potential Solutions

A Double Pivot

A fundamental problem for the United States was Sweden’s ability to have their cake and eat it to — they could both control Horan while harassing Sauerbrunn, hindering the center-back’s capacity to capitalize on the 3v2 by either passing or driving forward.

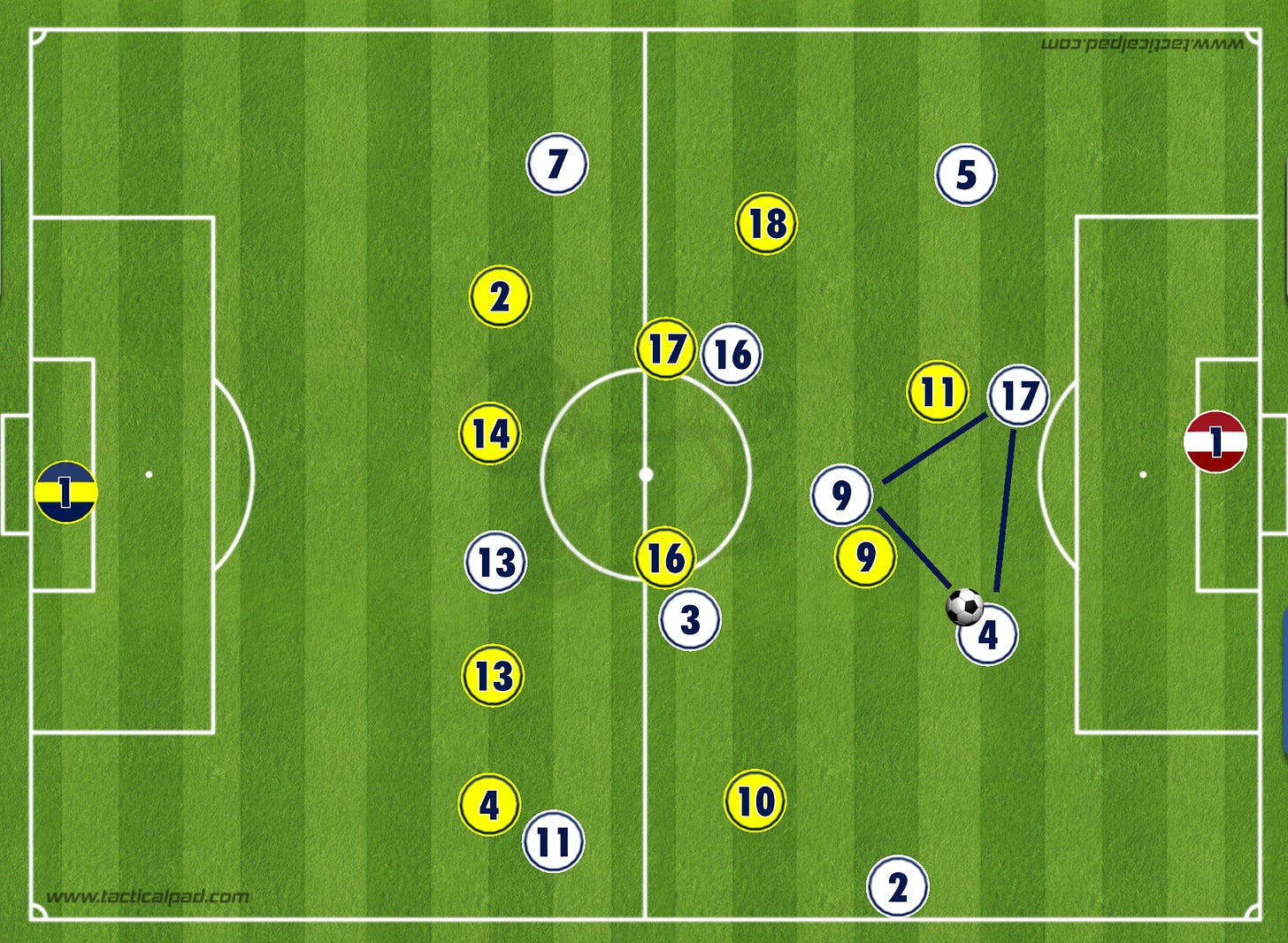

The idea of the double pivot is to mess with this dynamic, creating a 4v2 overload that becomes more challenging to cover.

This makes something like Mewis receiving to face play and initiate forward combinations much more of a threat, either requiring (1) Asllani or Blackstenius to block off a central midfield option or (2) Seger or Angeldal to push forward.

1) If Sweden choose to use Asllani to press Sauerbrunn and block off the LCM, the double pivot makes it easier to escape the cover shadow, as the far side central midfielder should dissuade Blackstenius from coming over and helping. The LCM can also push out to the wing, knowing that the RCM can come central, attracting Blackstenius and opening a lane to the far side CB, which destroys the sideline trap and allows easy switches of play.

2) If the latter occurs, the #10 can drag the remaining Swedish CM to a wide area, opening up a lane to a dropping striker, much like how we saw with Lloyd in the second half. The difference is in the deeper starting positions implied by a double pivot; a lot more ground needs to be covered in order to help out Asllani and Blackstenius, as opposed to the shorter spaces vs. the asymmetric 4-3-3. Hence, there should be time to get a central midfielder on the ball to make the pass — instead of the CB — thereby reducing the distance and difficulty of the delivery.

The former scenario is an absolute win for the US, as it disrupts Sweden’s largely player-to-player scheme — which allows only a singular 2v1 situation — into something that is far more zonal and complicated to control.

The second series of events isn’t bad either, but relies on tougher execution to find the player — who has to hold up the ball with a center-back on their heels — between the lines. Additionally, there is no guarantee that Seger or Angeldal remain content to launch a pressing action from deep, as one of them might simply decide to permanently position themselves higher up to gain greater access to the double pivot.

Ultimately, that would return the US to a similar situation in the second half and, again, puts a lot of onus on high-level execution. It’s better than the original context but, remember, Sweden are a highly adaptable and intelligent team that is full of capable 1v1 defenders. The ideal solution should create advantages that are relatively easy to pull off.

A Back Three

In my perpetual desperation to appear like a very smart individual, my caffeine-addled brain was obsessed with thinking of big-brain movements that would blow up Asllani’s double assignment and allow for clean progression.

It’s not unrealistic in the sense that there are defensive midfielders who are really good at this, such as Sergio Busquets and Maitane López Millán, but they’re also only two of a handful who can do it at a reasonably high level. Ertz is probably one of those other players, but she didn’t start because she wasn’t 100% fit.

Simplicity; ease — those are the tactical goals.

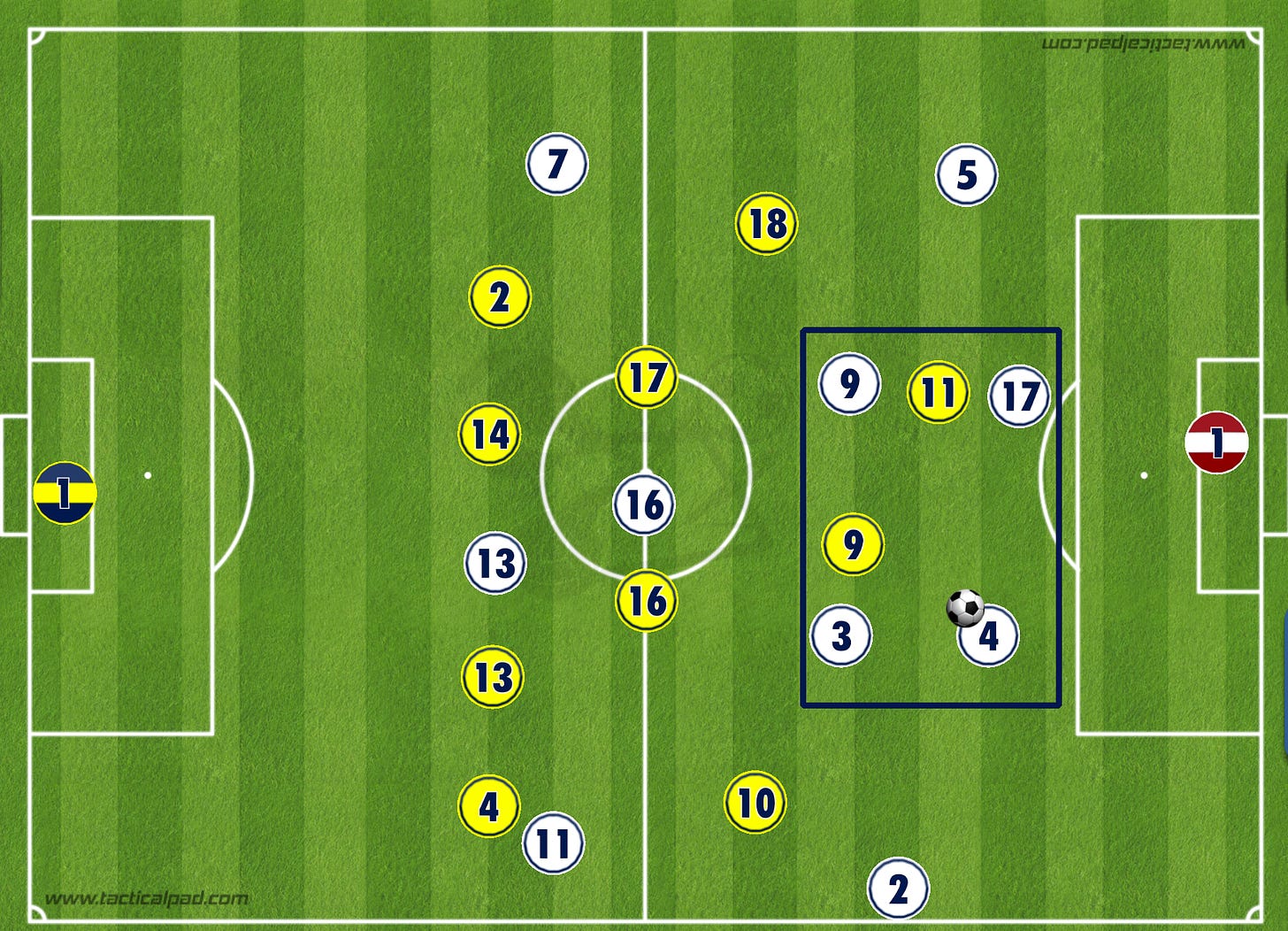

Instead of swashbuckling movements and ingenious passes from the sideline, what if the pivot simply dropped to create a back three?

By creating a flat 3v2 and stretching wide, the distances that Asllani and Blackstenius need to cover to be able to maintain pressing access become significantly larger, allowing for more time to receive and play a pass. And it’s not like the Swedish duo could simply station themselves on one wing preemptively (conceptually similar to one of Seger or Angeldal staying permanently higher up to address a double pivot), as that would allow an easy pass to the far side. Rather, they’d have to both guard the central outlet before then gravitating ball side.

This leaves the far side center-back unmarked and reachable through a quick switch of play using the goalkeeper, a long ball, or short passes, putting a lot of stress on Asllani and Blackstenius to move side-to-side and making a sideline trap harder.

Their job becomes more difficult when you consider that the pivot could step back into midfield at any time.

Of course, Sweden could counter by marking the far side CB with a winger, but that leaves a fullback free. This is not to say that accessing said free player is a piece of cake, but, at this point, we’ve reached a situation where Sweden have had to significantly alter their original strategy as a means of containing the US in deeper phases. As great as they are defensively, forcing Sweden into making a number of new calculations and decisions in an unplanned shape increases the potential for mistakes, and the USWNT generally only need a few to make rivals pay.

Concluding Thoughts

No one can say for certain how the game might’ve changed had the USWNT done this vs. Sweden. Even if it “worked,” a moment of individual brilliance or a mistake could’ve turned proceedings against the US. There are also an innumerable number of variables that have yet to be considered, such as whether Alyssa Naeher could’ve kept her composure passing to the far side when pressed.

Furthermore, there are definitely other variations to consider: a fullback dropping to create a back three, etc.

However, this type of thinking is necessary if the USWNT are to avenge a humiliating 3-0 defeat later down the line. I’m not saying that this article has the perfect answer, but I believe that I have demonstrated a reasonable logic to arrive at the right solution against an opponent that is incredibly formidable in their preferred defensive structure.

Identify the opposition tactic as accurately as possible:

4-4-1-1 sideline trap.

Shut off access to the single pivot.

Disrupt the strategy:

Free up the single pivot.

Escape sideline trap.

Make the solution relatively easy to execute:

Form a back three with the pivot.

Use increased width in back line to access far side.

Agree? Disagree? Let me know.