How Basketball Can Help Us Understand Football: Introducing 'Floor Raising' & 'Ceiling Raising'

Why buying a bunch of superstars doesn't always work.

Drawing from other sports to help us better understand our own isn’t particularly new. Both football and hockey have influenced each other over time through the adoption of expected goals (xG), and some of the most innovative set-piece routines incorporate what looks suspiciously like “screens” from basketball.

It is that latter sport where I think a lot can be drawn from — less because it’s incredibly similar to football and more because of the amazing analytical and conceptual work that is being done in that space.

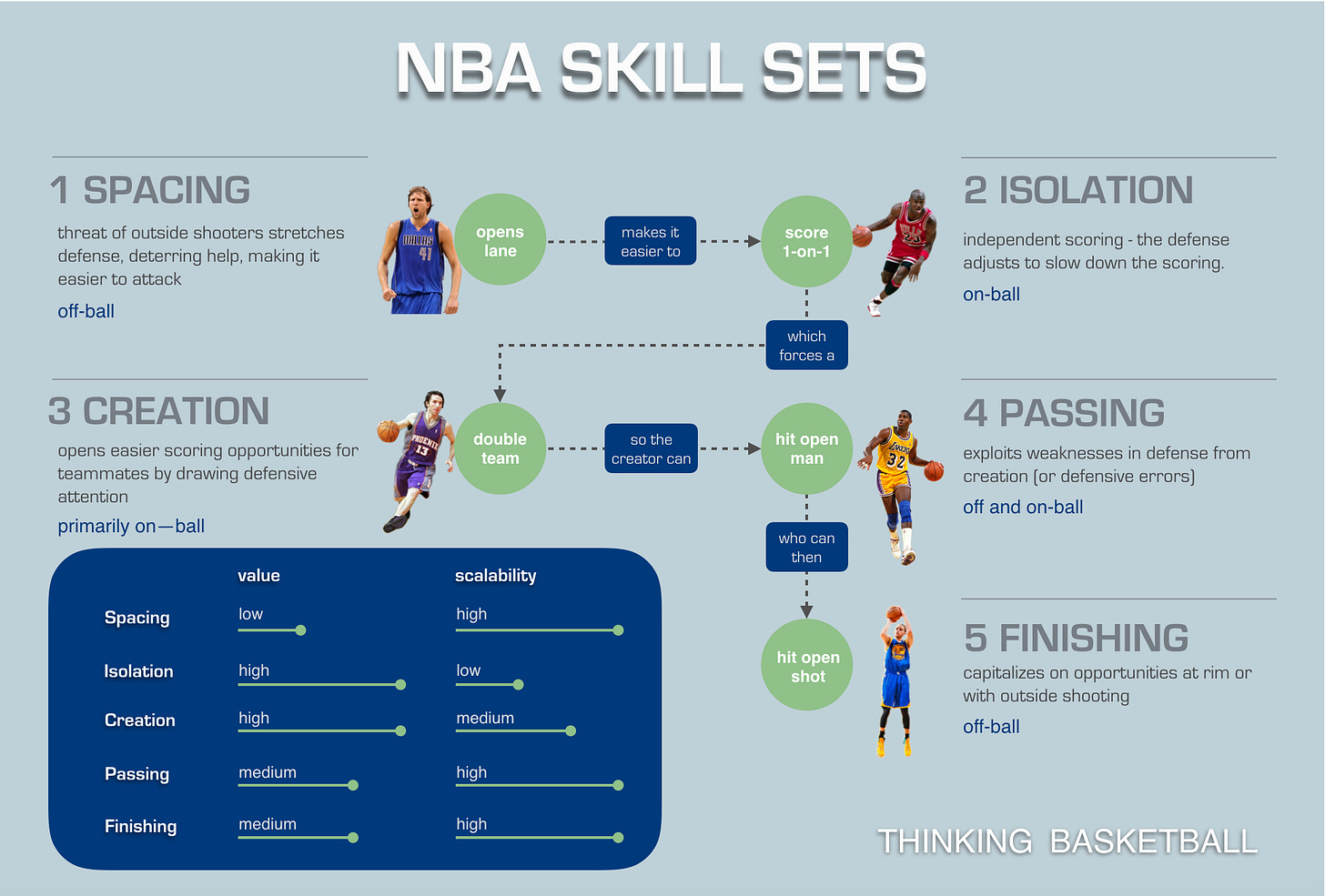

Take Ben Taylor, who made the best all-time list I’ve seen with his “Backpicks Top 40.” In it, he lays out his comprehensive logic for player evaluation, part of which includes a concept called “portability” (or “port” for short, often interchanged with “scalability”):

Portability — a termed inspired by the portable document file (PDF), meant to be read in varying hardware and software environments — is about interfacing in different basketball environments. More specifically, it’s about players maintaining impact, or scaling up, on better and better offenses, which is critical when building championship-level teams [emphasis added].

That definition comes from a 2018 article, where he used port to explain why the “big three” of Russell Westbrook, Carmelo Anthony, and Paul George didn’t work out as expected for the Oklahoma City Thunder.

When integrated back into a holistic analysis of player impact, Ben was able to drill down on the skill sets that made certain players more valuable on better teams.

Portability, in conjunction with a clear understanding of relevant skill sets, can be taken further to create offensive archetypes — namely “floor raisers” and “ceiling raisers” — that categorize players based on this logic.

In short, the best floor raisers in basketball are those who tend to be ball-dominant, capable of turning their many possessions into volume scoring (Michael Jordan) and creation for others (Magic Johnson). These are the guys who can take largely mediocre teammates to the NBA Finals by taking all the shots or elevating role players or both (LeBron James).

You extract the most value out of this archetype by letting them run the show and make all the decisions.

The best ceiling raisers in basketball are usually capable of operating off-ball and/or offer spacing via a shooting threat. They are extremely good at finishing off chances provided to them, whether that be through alley-oops (Anthony Davis) or dishes to set up an attempt from beyond the arc (Steph Curry). Their “gravity” without the ball manipulates defenses. These are the guys who make already great teams even better.

You extract the most value out of this archetype by putting them next to elite players who are probably ball-dominant.

The reason that this is all so important is that it has major implications for roster construction. A so-called “star” might not provide a team with the expected value if they’re paired with un-complementary co-pilots, which can be hugely problematic if large sums of money went into building the side that way.

This is of special concern in football, as the sport staggers out of a global pandemic and old powerhouses like Real Madrid and Barcelona face severe financial limitations as a result.

Translating the Concepts to Football (Focusing on Attackers)

Firstly, it is important to note that I am not the first person to attempt this translation. Mohamed Mohamed has written many excellent historical player profiles that use these concepts, which have also filtered into niché football Twitter and are discussed intermittently by some people you probably follow.

If your eyes can’t bear anymore text, you can hear Mohamed and Carl Anka discuss these terms on their OG Ronaldo podcast.

Nevertheless, I do believe that this is the first attempt at ~fully laying out what portability, floor raising, and ceiling raising look like in football. If not, I sincerely apologize for my hubris and would be happy to link to other works. Hit me up on Twitter or in the comments if you know of anything I’ve missed.

The Differences

Football, obviously, is a very different sport from basketball. For one, there are twelve more players on the field at any given point in time and positions are more fixed in the former.

Sure, there is delineation by “role” in basketball — point guard, shooting guard, small forward, power forward, center — but there is rarely strict restrictions (imposed either by the player’s preferences or coaching instruction) on the spaces one can occupy. Left, right, middle — most hoopers float through all parts of the court over the course of a game.

By contrast, a left back will rarely ever move to the other side of the pitch and certain players prefer to operate solely in particular areas.

There are two things that can be taken from this when applied to football:

1) The greater number of players naturally decreases the share of touches a star can have.

2) Positional and spatial versatility is a skill in and of itself.

Portability in Football

This means that portability is different in football. For one, the more balanced distribution of touches implies that ball dominance is not as, well, dominant as it is in basketball, though it still exists and is relevant.

On the other hand, positional and spatial versatility are a lot more significant than they are in basketball, and signing someone who is as comfortable on either flank as they are in the center increases their chances of meshing well with other talent.

Stemming from that logic, here are the key traits and skills that make portable football attackers, ordered by their importance to scalability (this is definitely up for debate):

Off-ball movement: running beyond the last line, advanced positioning/resisting coming to the ball, and box movement; they all have an effect on opponent defensive structure even if the person making these motions never gets possession (off-ball gravity).

Positional versatility and diverse spatial occupation, which allows a coach to deploy a player in multiple different formations and attacking set-ups. Aided by two-footedness.

Good passing, including “connective tissue” link-up and combination play.

Pressing and defensive work-rate.

Aerial ability.

Together, this combination of attributes should allow an attacker to make most top-level sides in world football better.

To help you better understand my argument and criteria, let’s dive into some examples and case studies, framed by the previously discussed archetypes: floor raising and ceiling raising.

Floor Raising

When trying to figure out what a floor raiser in football looks like, look no further than perhaps the greatest ever example of the archetype: Lionel Messi. Despite a continually deteriorating roster since ~2017, Barcelona won two league titles in a row from 2018-2019 and had by far the best offense in the 2021 edition of La Liga.

His GOAT-level dribbling/carrying, passing, and shooting was the reason for this, allowing him to be a one-man progression and goal creation machine. He elevates Barça by constantly demanding the ball, optimizing decision-making and execution by ensuring that he is the one doing the deciding and executing. With 27 non-penalty goals and 9 assists, Messi had a direct hand in just under 50% of the 76 non-penalty goals (excluding own goals) his side netted in the league.

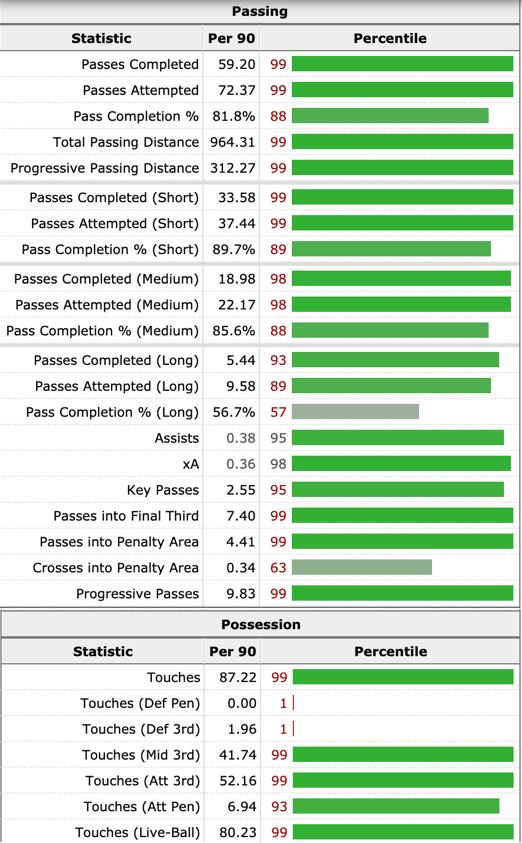

Whether vs. forwards or attacking mids/wingers, Messi consistently ranks in the 99th percentile (or thereabouts) for passing and progression volume and overall touches.

However, this is not necessarily all down to pure need. As Dani Alves once noted, Messi has to have the ball to feel comfortable:

With Guardiola, I had a lot of problems with first-touch football. I always tried to link up with Messi but Guardiola got angry. One day I told him: “I don't accept your complaints. If Messi doesn't touch the ball for two minutes, he disconnects from the match. If we're going to prepare a style which defines our play, he always needs to be connected to it. Then he can link up with the rest of us.”

Pep told me: “You're right.” These type of players always need to be on the ball.

This was back when Messi still played next to some of the greatest playmakers and controllers in the world.

It’s also worth pointing out that Messi’s game has always been heavily oriented in the right halfspace, something that has become more extreme as the seasons have passed and he’s dropped deeper and deeper.

Per John Muller from an old piece that will become relevant very quickly:

Messi’s drift has had knock-on effects across the squad, as Valverde has looked for ways to spread his attack by rotating workhorse midfielders like Paulinho and Arturo Vidal to the front line or stretching Sergi Roberto to his breaking point up and down the right flank. It’s also changed the way the other forwards operate. Suárez plays a little farther left than he used to, sometimes slipping outside the centre backs to open a channel for Messi. When Ousmane Dembélé starts, the two-footed winger is as likely to line up outside Messi to the right as he is on the left wing, where an overlapping Jordi Alba is Messi’s preferred target. As for Philippe Coutinho, he’s suffered carrying the ball into Barça’s clogged middle without the skill to combine in tight spaces. It’s hard out there for all these €120+ million attackers just trying to fit in.

Knowing this, who did Barcelona buy to reinforce their offense in the summer of 2019?

This guy:

Antoine Griezmann lived in the right halfspace at Atlético Madrid, helping lift a poor offense to semi-respectable levels. Sound like someone?

In essence, Barcelona paid €120 million for a player who did Messi’s job worse and in the exact same part of the field. Oh, yeah, Griezmann also reportedly earns anywhere from €25-45 million annually — good for second (or third) most on the team.

The results in 2019/20 were suboptimal. He was shunted out wide to the left, collecting a paltry 13 goals+assists in 2,549 league minutes.

Analytics writer and fellow newsletter lad John Muller predicted this in his aforementioned Statsbomb article: Barcelona’s Griezmann Signing Makes No Damn Sense.

Playing in a strike duo up top the following season and having a slightly better understanding with Messi brought better results for the Frenchman: 19 goals+assists in 2,604 La Liga minutes, but it’s hard to argue that Barcelona couldn’t get better production from a “proper” striker who seeks to stretch lines — you know, the stuff a portable attacker does.

Speaking of portability, there’s a reason that the young Pedri is such a good fit next to Messi. Termed the “positionless prodigy” by one of my favorite Barcelona content creators, Sam Gustafson, his ability to operate in the left halfspace while staying between the lines has created a fantastic synergy between the kid and the mercurial Argentinian.

Pedri specializes in the type of quick combinations/”connective tissue” passing that makes him the perfect foil for Messi’s desire to initiate from deep.

To top it off, Pedri works his ass off defensively, too. He ranks #1 in total pressures, #1 in attacking third pressures, #1 in middle third pressures, and #4 in defensive third pressures within the squad per fbref. As Messi’s already minimal defensive load will only decrease as the years pass, Pedri is the type of player who makes it viable to keep revolving everything around a wildly talented but aging superstar who only allows particular archetypes to thrive next to him.

The Lesser but More Portable Floor Raiser

There is an offensive archetype that falls in a curious place. They embody the traditional floor raising pattern of becoming more productive when supplemented by good off-ball movers but lack the extreme ball-dominant tendencies that would hinder their portability.

They are the #10/advanced playmaker — the ones that operate primarily inside opponent’s defensive structures and manufacture their value almost entirely through their ability to elevate others through chance creation. Their floor raising can reach even greater heights if their dribbling ability and self-creation are strong, but their inclination to stay high means that it’s easier to deny them the ball.

As a result, their influence can differ wildly from game-to-game based on whether they get enough touches or not, though they retain a solid level of off-ball impact based on how they pressure opponents’ defensive compactness. This is comparable to pinning defensive lines back — though there is still an emphasis on receiving to feet — but is probably not as impactful as creating shots through box movement, hence capping this archetype’s portability at a certain level.

Mesut Özil is the prototypical example of this and his career arc represents how this archetype’s creation-focused production can be less resilient than a Messi-type floor raiser. At Real Madrid, Özil achieved bonkers shot facilitation numbers, hitting 4+ key passes p90 in the league in two of his three seasons, and averaged 20 assists across the Champions League and La Liga.

2015/16 was his only season at Arsenal where he came close to matching his p90 shot facilitation and overall assist numbers. Was this because he magically got worse or played with talent that was significantly inferior at finding him between the lines and creating movement for him to hit? Regardless, he didn’t have his own scoring game to compensate.

Özil was often slammed for being an outrageously difficult player to accommodate — what with the supposed death of the classic #10 and all. However, I think his ability to aid ball progression from deep is underestimated, giving him further floor raising value and positional versatility (ability to play as an interior in a 4-3-3 in on-ball situations). The bigger issue is his defensive work-rate, which is why this archetype has evolved to look something more like Martin Ødegaard.

Though not on the same level when it comes to receiving on the half-turn and sheer passing genius, Ødegaard is the type of player who can appear to shrink in influence if not found between the lines. He mitigates this somewhat by being a hybrid #10/#8 who offers a lot as a ball progressor and is an active presser, which makes him a more practical option in deeper midfield positions against a wider variety of opponents, unlike Özil.

This type of player requires a special type of environment to be at their best but can be worth making room for due to their mix of positional discipline and chance creation, which allows them to floor raise without stepping on other’s toes. Even so, they are unlikely to reach the raw peak of a goal scoring floor raiser nor be as impactful in progression as a deeper ball player, which is part of why this archetype has been largely subsumed under the deep-lying forward/false nine, attacking #8, and inside forward roles.

Ceiling Raising

When Cristiano Ronaldo departed Real Madrid in 2018, there was some debate about whether he needed any replacing at all. Those who didn’t think so banked on the idea that Ronaldo “stole” offense from other players — likely due to his volume shot numbers — meaning that the likes of Karim Benzema, Gareth Bale, Marco Asensio, etc. would be finally freed to pick up the slack.

Though there were some other causes for the struggles in 2018/19, it’s safe to say that things haven’t quite panned out that way. Benzema has done an incredible job since then, acting like Messi-lite for Real Madrid, but his non-penalty xG (npxG) numbers saw no real uptick from 17/18 until this season. Even then, his 20/21 figure of 0.53 p90 pales in comparison to the 0.93 he racked up in 15/16 and the 0.63 he earned the following campaign [note: all xG figures pre-17/18 are taken from understat] — seasons when he played with Ronaldo.

That might be a shocking revelation for some, but Ronaldo fits the mold of a portable attacker who would make a good team like Real Madrid great without taking much away from others. Unlike his younger self, he’s far less concerned with getting lots of touches, especially in deeper areas, and is instead obsessed with leveraging his all-time box movement and athleticism to obtain high quality attempts on goal. Next to Benzema and his floor-raising tendencies, the duo formed a mutually beneficial — rather than predatory — partnership.

As his ability to self-generate offense and create for others had declined significantly since ~2015, Ronaldo’s overall output at Juventus fell off in concordance with playing next to worse creators. Some of that could no doubt be down to natural decline, but it feels difficult to argue that 2018/19 Ronaldo was that much worse than his prior self, especially without any major injury problems and a lack of further, noticeable drop-offs in athleticism.

Not to belabor the endless contrasts between the two, but Ronaldo feels like he belongs on the opposite end of the spectrum to Messi in this respect, though I wouldn’t say that late stage Ronaldo is the perfect example of a ceiling raiser.

His combination play and passing has its flaws and his inability to operate as a lone striker nor defend with any gusto makes squad construction around him more challenging than it may seem at face value. This is why Juve held onto old Gonzalo Higuaín, took a leap of faith with Alvaro Morata, and used to regularly feature the energetic Blaise Matuidi in left central midfield despite his obvious ball-playing deficiencies.

You either have to play Ronaldo out on the left, where he offers little of the carrying, line-breaking, and chance creation of years past, or be locked into a two-striker system so someone can regularly occupy the defensive line and do center forward duties outside the box.

So, who should be the poster child of ceiling raising?

Capable of leading the line all by himself, possessing above average link-up and passing, and an absolute terror in the box with his movement and aerial ability, Robert Lewandowski is the ultimate ceiling raiser. Stick better and better high-level creators around him and he only becomes more likely to find the back of the net.

Dominic Calvert-Lewin is a more contemporary example. Profiled in this excellent piece by Mustafa, DCL is akin to Lewa thanks to his good first touch, enabling him to link efficiently and quickly with others, though he doesn’t demand ball to feet regularly like a Benzema or Messi. Instead, he prefers to pin the defensive line back with his positioning, creating space for others to operate, and makes his money in the box.

Similar to Lewandowski and Ronaldo, he is generationally good in the air, which has outlying value for elite teams who tend to dominate the ball and, thus, face packed defenses who force lots of crosses. Consequently, DCL’s 0.48 npxG p90 and 16 non-penalty goals in the league probably undersell his value and what he can do if gifted better teammates.

Who Has it All?

Does everything have to be a compromise? Is there anyone out there who checks all the boxes as an elite floor raiser and ceiling raiser?

Ladies, gentlemen, and non-binary folk, let me introduce you to a little known player called Kylian Mbappé.

Tremendously adept at receiving between the lines and combining through quick one/two-touch passing, an all-time ball carrier, and high-quality chance creator for both himself and others, Mbappé has the traits of a supercharged attacking midfielder who also happens to be just as comfortable occupying the last line and threatening off-the-shoulder.

Just for kicks, he’s basically equally comfortable as a left-winger, striker, or right-winger.

Put him next to Messi 2.0 in Neymar and Mbappé’s fine being a ceiling raiser. Play him without Neymar (which has been quite frequent due to injury) and Kylian’s there to do some heavy-lifting as well.

The one catch?

I guess you can’t have it all.

Conclusion

While I attempted to lay out a framework for portability in football by analyzing examples of floor raising and ceiling raising for attackers, this is very much a work in progress — a discussion-starter rather than a theoretical manual. I was stuck for hours on Özil, originally classifying him as a “ceiling-ceiling raiser” (whatever the fuck that is) before I was able to find some clarity.

There’s still a decent possibility that I got it wrong.

What I hope is that I got you thinking about skills and characteristics that make certain footballers more likely to elevate better teams. It should be clear by now that stacking random stars on top of each other doesn’t necessarily work and the way their tendencies and traits match up is vital to creating an optimal offensive system.

Let me know if I’m heading in the right direction or whether I got you thinking of other examples right here in the comments or on Twitter.